Quick Navigation:

| | |

Chapter 4: Structure of the Atom

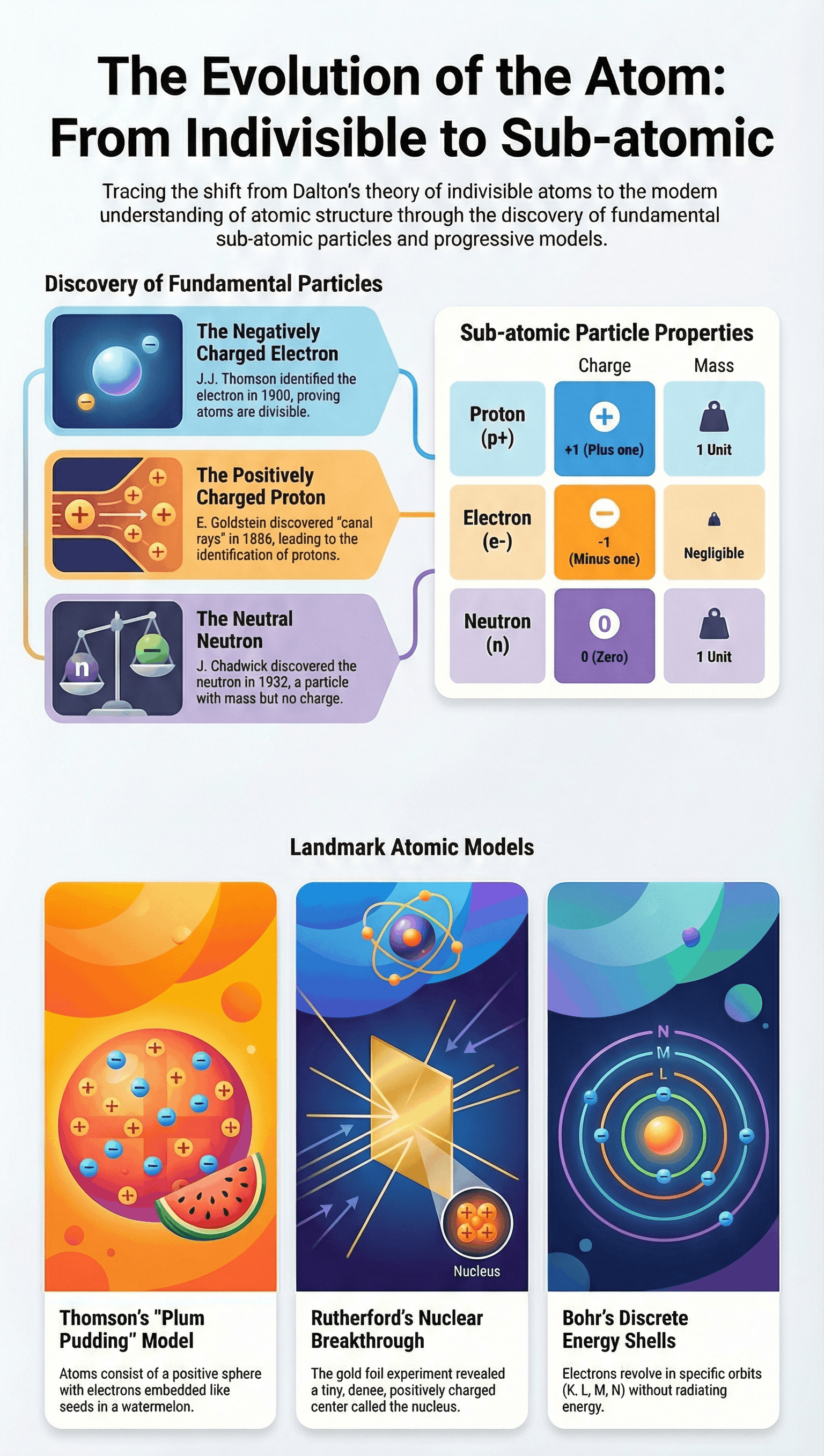

1. Discovery of Charged Particles

- Introduction: Early experiments with static electricity suggested that atoms are divisible and consist of charged particles.

- Canal Rays: Discovered by E. Goldstein in 1886. These were positively charged radiations in a gas discharge which led to the discovery of the proton.

- Electrons: Identified by J.J. Thomson. They are negatively charged sub-atomic particles.

- Protons: Positively charged particles. A proton has a charge equal in magnitude but opposite in sign to that of an electron. Its mass is approximately 2000 times that of an electron.

- Comparison: An electron is represented as e⁻ (charge -1, negligible mass) and a proton as p⁺ (charge +1, mass 1 unit).

2. Atomic Models

A. Thomson’s Model of an Atom

- Comparing an atom to a Christmas pudding or a watermelon.

- The atom is a positively charged sphere with electrons embedded in it (like seeds in a red watermelon).

- The negative and positive charges are equal in magnitude, making the atom electrically neutral.

- Limitation: It could not explain the results of experiments carried out by other scientists (like Rutherford's).

B. Rutherford’s Model of an Atom

The Gold Foil Experiment: Fast-moving alpha particles (doubly-charged helium ions) were bombarded on a thin gold foil.

- Observations:

- Most alpha particles passed straight through the foil.

- Some were deflected by small angles.

- Surprisingly, one out of every 12,000 particles rebounded (deflected by 180°).

- Conclusions:

- Most space inside the atom is empty.

- The positive charge occupies very little space.

- All the positive charge and mass are concentrated in a very small volume called the Nucleus.

- Features of the Nuclear Model: Electrons revolve around the nucleus in circular paths. The nucleus is very small compared to the atom.

- Drawback: Orbital revolution of a charged particle is not stable. The electron would undergo acceleration, radiate energy, and eventually fall into the nucleus, making matter unstable.

C. Bohr’s Model of an Atom

- Proposed by Neils Bohr to overcome objections to Rutherford’s model.

- Only certain special orbits known as discrete orbits of electrons are allowed inside the atom.

- While revolving in these discrete orbits, electrons do not radiate energy.

- These orbits are called energy levels or shells, represented by letters K, L, M, N... or numbers n=1, 2, 3, 4...

3. Neutrons

- Discovered by J. Chadwick in 1932.

- A sub-atomic particle with no charge and a mass nearly equal to that of a proton.

- Present in the nucleus of all atoms except Hydrogen.

- The mass of an atom is the sum of the masses of protons and neutrons in the nucleus.

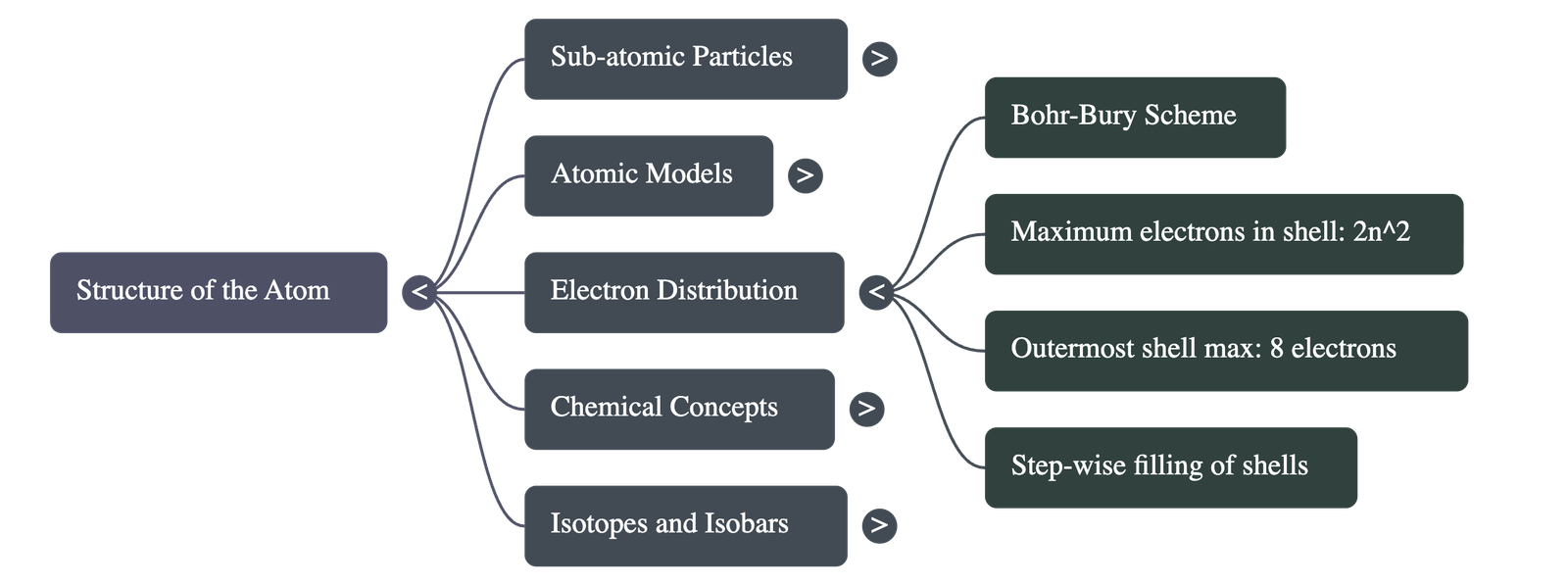

4. Distribution of Electrons and Valency

- Bohr-Bury Scheme: Rules for filling electrons in shells.

- Maximum Electrons: The maximum number of electrons in a shell is given by the formula 2n² (where 'n' is the orbit number).

Examples: K-shell (n=1) = 2; L-shell (n=2) = 8; M-shell (n=3) = 18. - Outer Shell Limit: The maximum number of electrons that can be accommodated in the outermost orbit is 8.

- Filling Order: Inner shells must be filled before outer shells (step-wise manner).

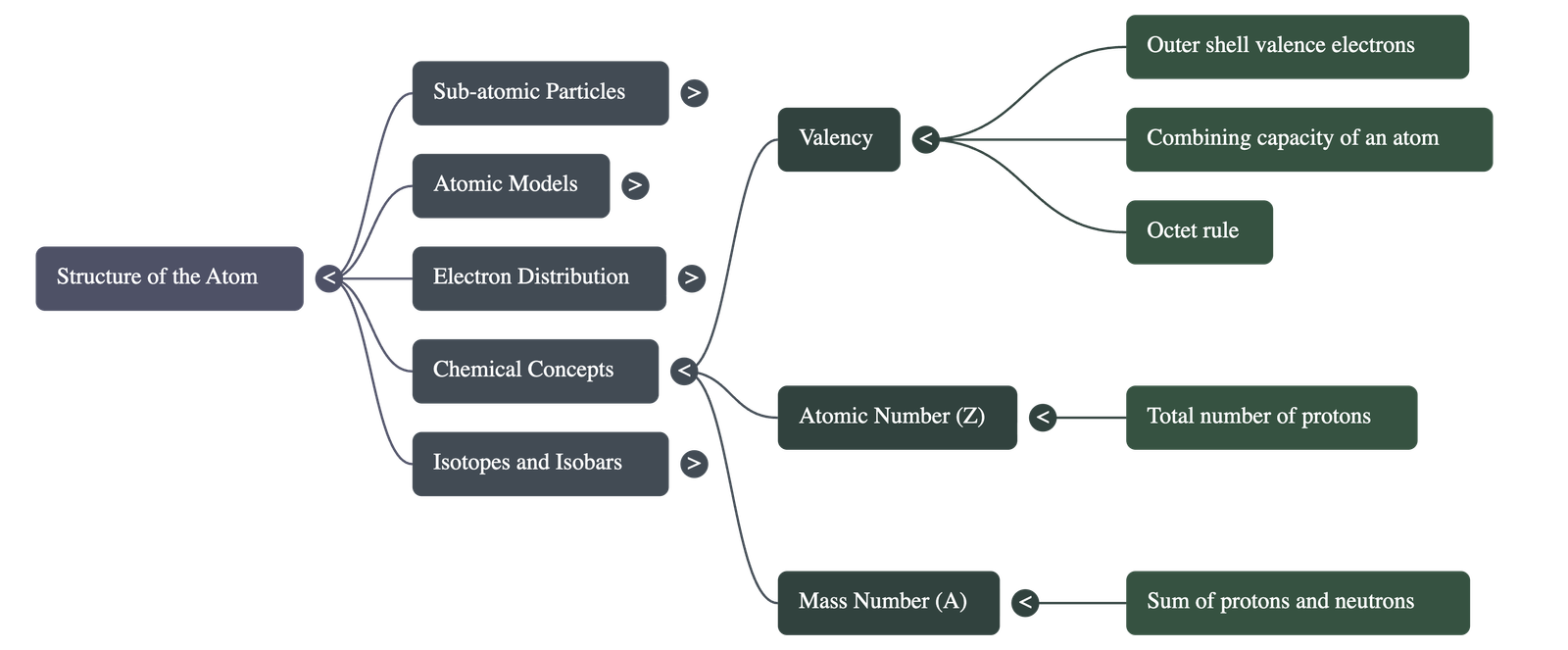

- Valency: The combining capacity of an atom. It is determined by the number of valence electrons (electrons in the outermost shell).

- Atoms with 8 electrons in the outer shell have an octet and are chemically inert (zero valency).

- Atoms react to achieve a fully filled outer shell by losing, gaining, or sharing electrons.

- Calculation: If outer electrons ≤ 4, Valency = number of electrons. If outer electrons > 4, Valency = 8 minus number of electrons.

5. Atomic Number and Mass Number

- Atomic Number (Z): The total number of protons present in the nucleus of an atom. Elements are defined by their atomic number.

- Mass Number (A): The sum of the total number of protons and neutrons present in the nucleus. Protons and neutrons are collectively called nucleons.

- Notation: An atom is represented with Mass Number (A) as superscript and Atomic Number (Z) as subscript (Example: ¹⁴N₇).

6. Isotopes and Isobars

- Isotopes: Atoms of the same element having the same atomic number but different mass numbers (same protons, different neutrons).

Examples: Hydrogen has three isotopes: Protium, Deuterium, and Tritium. Carbon has ¹²C and ¹⁴C. Chlorine has ³⁵Cl and ³⁷Cl. - Average Atomic Mass: For elements with isotopes, the atomic mass is the weighted average of the masses of the naturally occurring isotopes. (e.g., Chlorine is 35.5 u).

- Applications of Isotopes:

- Uranium isotope: Fuel in nuclear reactors.

- Cobalt isotope: Treatment of cancer.

- Iodine isotope: Treatment of goitre.

- Isobars: Atoms of different elements with different atomic numbers that have the same mass number (total nucleons are the same).

Example: Calcium (Atomic Number 20) and Argon (Atomic Number 18) both have a Mass Number of 40.

Summary based on NCERT Science Chapter 4.

Quick Navigation:

| | |

1 / 1

Quick Navigation:

| | |