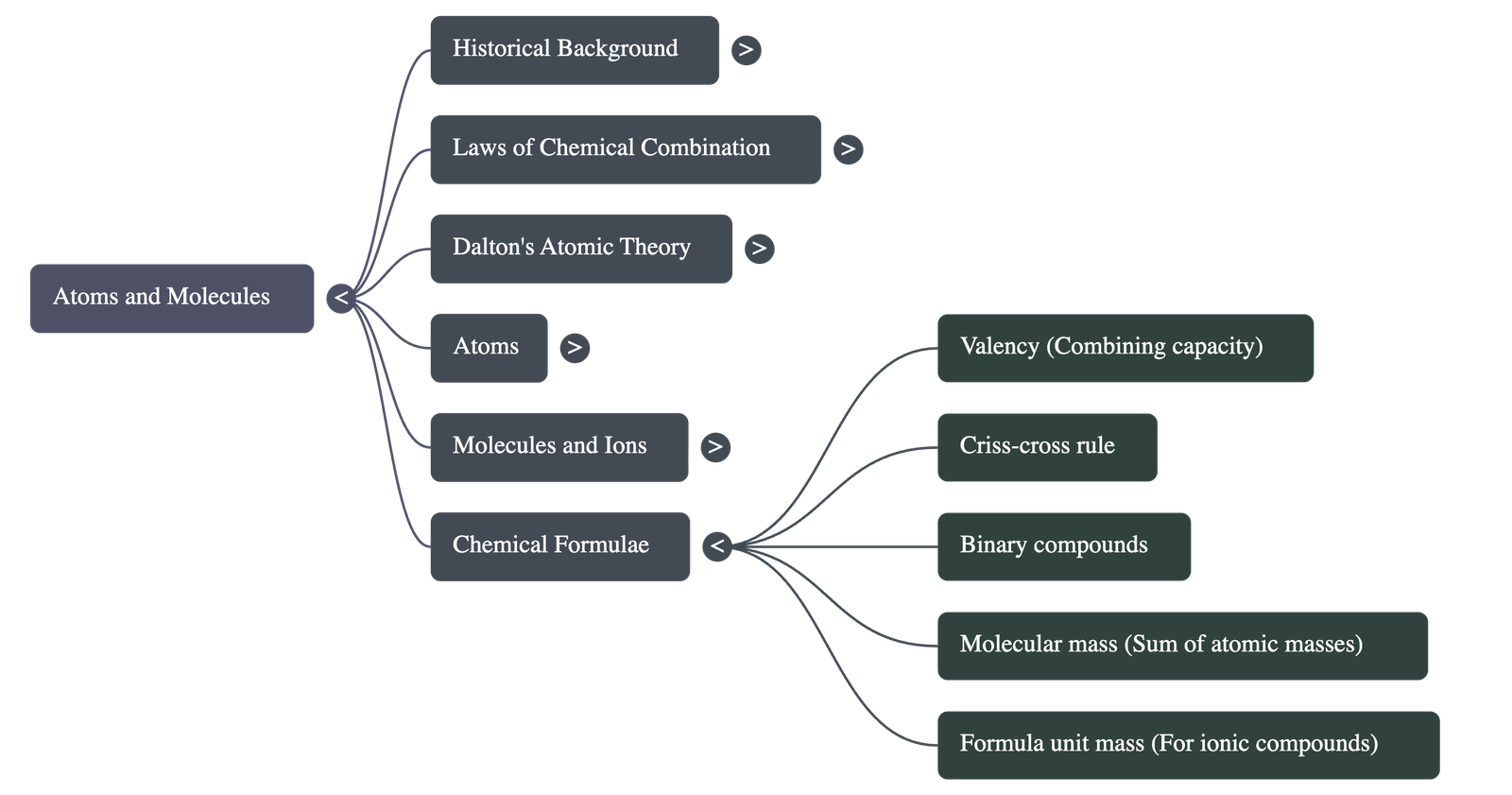

Chapter 3: Atoms and Molecules

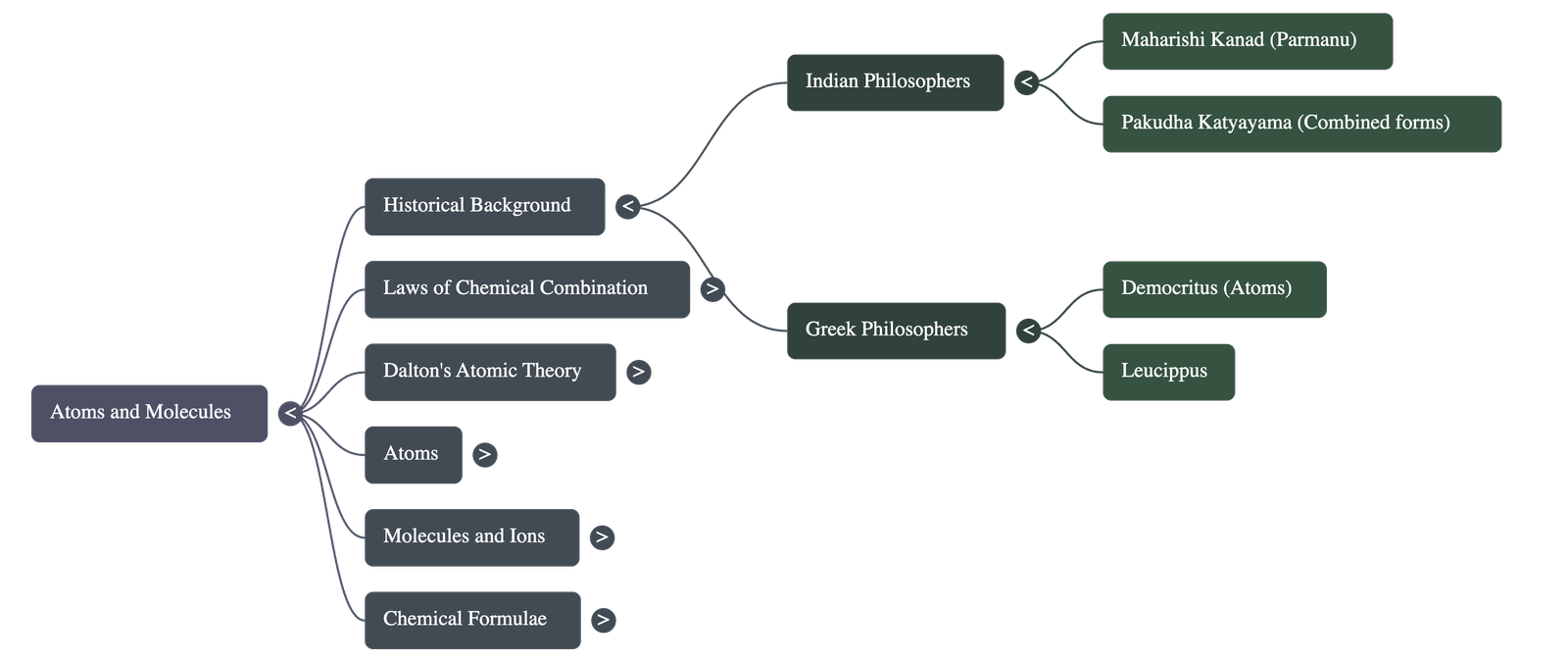

1. Historical Context and Philosophy

- Indian Philosophy (500 BC): Maharishi Kanad postulated that dividing matter (padarth) eventually leads to the smallest particles called Parmanu, which cannot be divided further. Pakudha Katyayama suggested these particles exist in combined forms to create various types of matter.

- Greek Philosophy: Democritus and Leucippus suggested that dividing matter results in indivisible particles called atoms (meaning indivisible).

- Scientific Era: By the end of the 18th century, scientists moved from philosophy to experimental validation, distinguishing between elements and compounds.

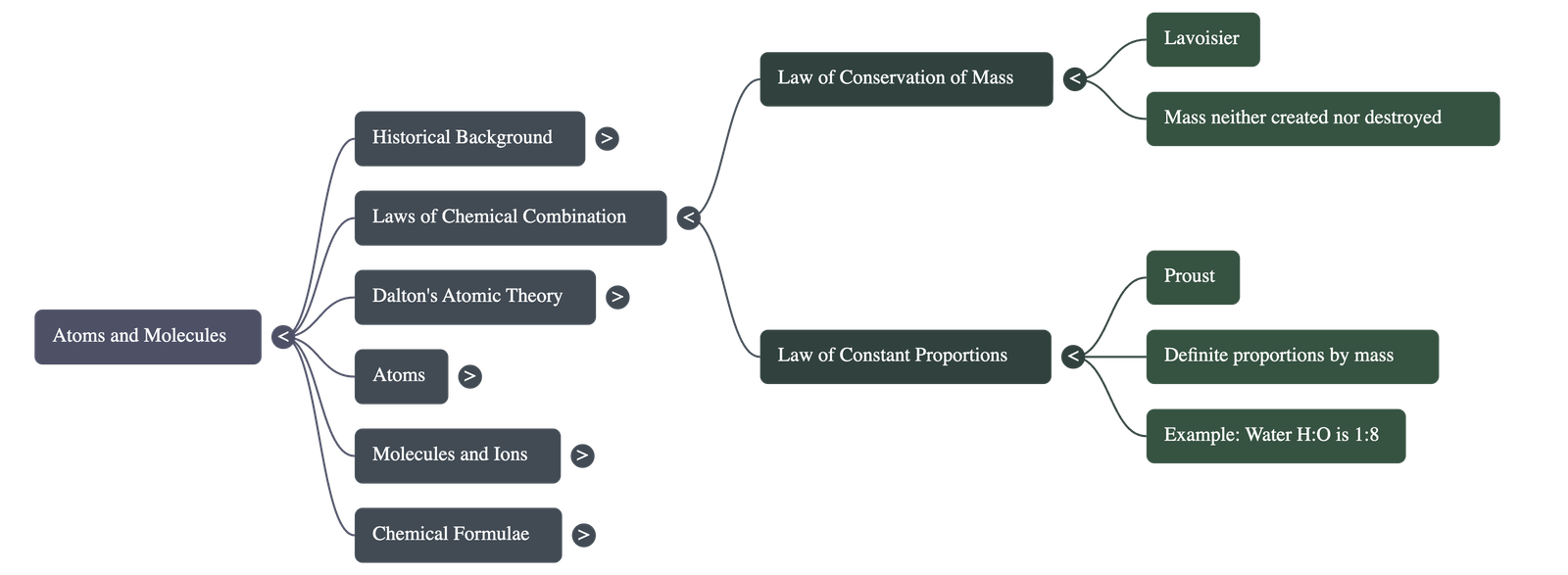

2. Laws of Chemical Combination

Antoine L. Lavoisier and Joseph L. Proust established two fundamental laws after extensive experimentation:

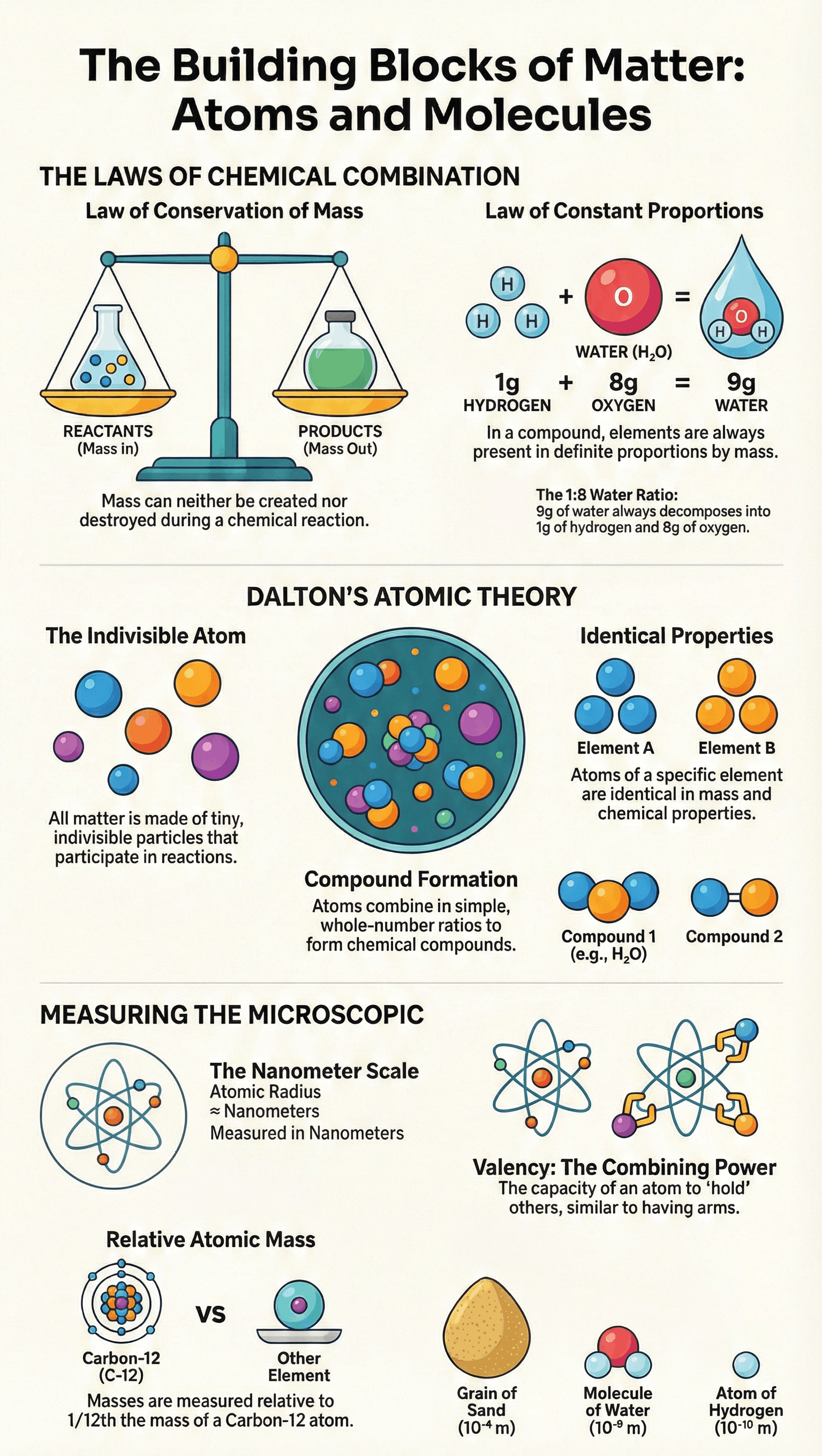

A. Law of Conservation of Mass

Mass can neither be created nor destroyed in a chemical reaction. The sum of the masses of reactants equals the sum of the masses of products.

B. Law of Constant Proportions (Law of Definite Proportions)

In a chemical substance, the elements are always present in definite proportions by mass.

- Example (Water): The ratio of the mass of hydrogen to oxygen is always 1:8, regardless of the source.

- Example (Ammonia): Nitrogen and hydrogen are always present in the ratio 14:3 by mass.

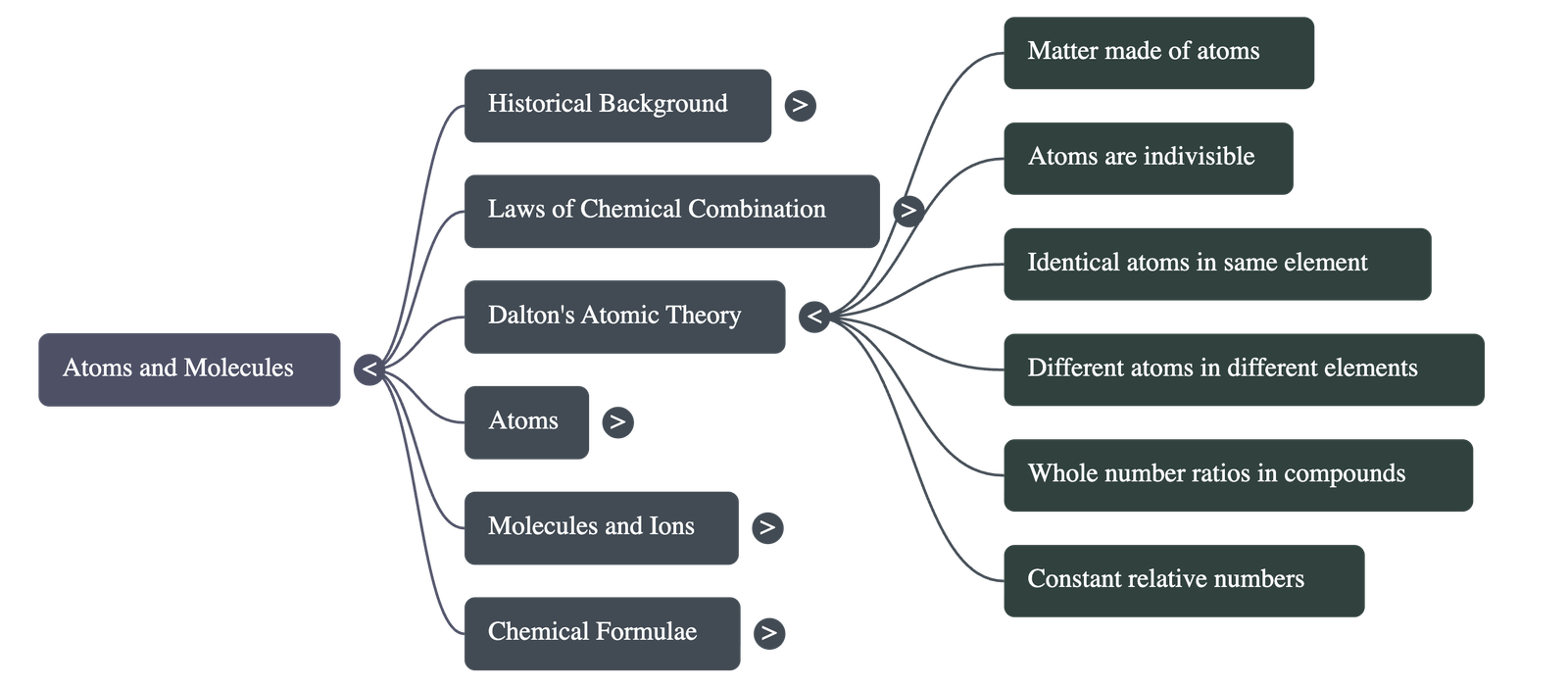

3. Dalton’s Atomic Theory

British chemist John Dalton provided a theory explaining the above laws, defining atoms as the smallest particles of matter. His postulates are:

- All matter is made of tiny particles called atoms.

- Atoms are indivisible particles that cannot be created or destroyed in a chemical reaction (explains Conservation of Mass).

- Atoms of a given element are identical in mass and chemical properties.

- Atoms of different elements have different masses and chemical properties.

- Atoms combine in the ratio of small whole numbers to form compounds.

- The relative number and kinds of atoms are constant in a given compound (explains Constant Proportions).

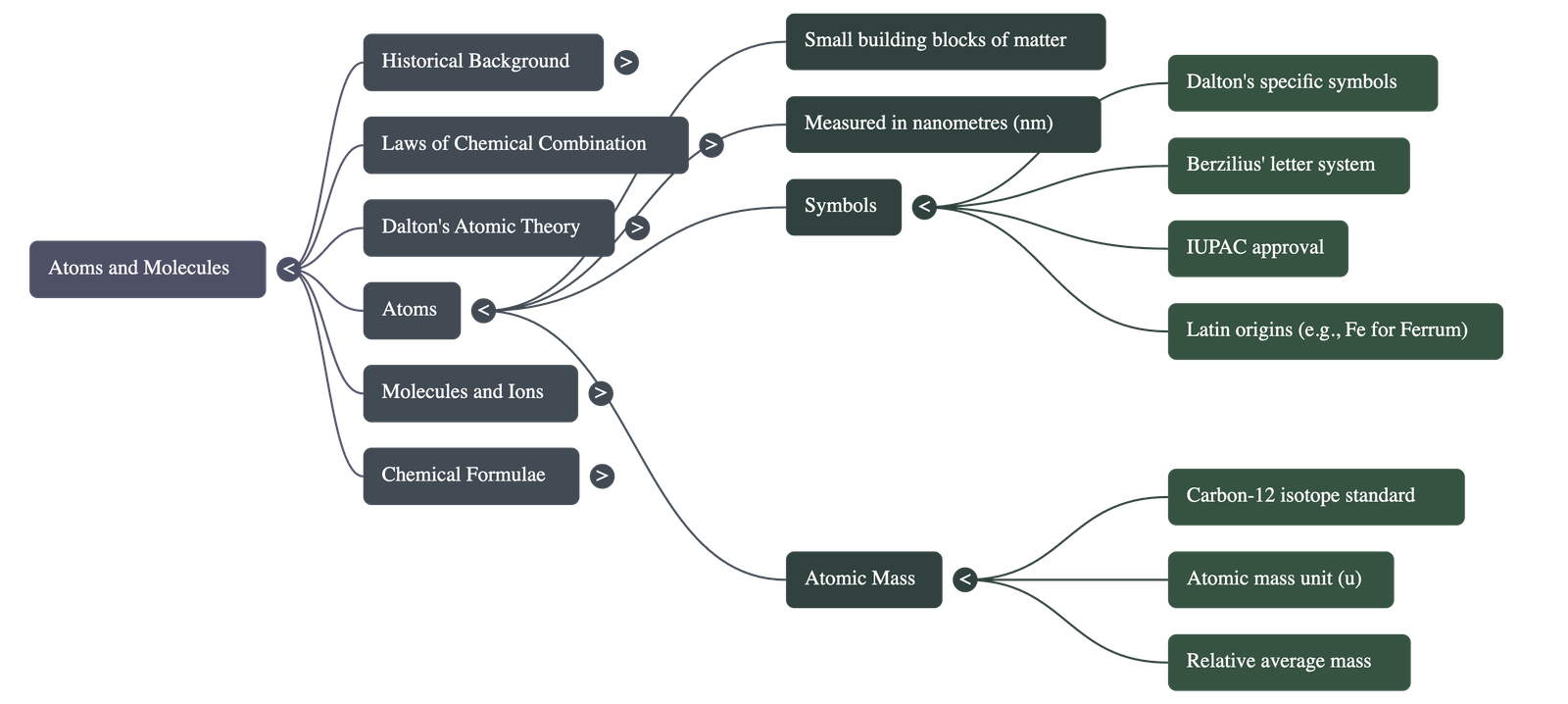

4. What is an Atom?

Size: Atoms are incredibly small, measured in nanometers (1 nm = 10-9 m). Millions of atoms stacked equal the thickness of a sheet of paper.

Symbols of Elements

- Dalton: Used specific pictorial symbols.

- Berzilius: Suggested using one or two letters of the element's name.

- Modern IUPAC Symbols: The first letter is uppercase, the second is lowercase (e.g., Aluminium is Al, not AL).

- Origins: Some symbols come from English names (Hydrogen: H), while others come from Latin (Iron: Fe from ferrum; Sodium: Na from natrium; Potassium: K from kalium).

Atomic Mass

- Each element has a characteristic atomic mass.

- Standard Reference: Carbon-12 isotope (chosen in 1961).

- Definition: One atomic mass unit (u) is a mass unit equal to exactly one-twelfth (1/12th) the mass of one atom of carbon-12.

- Relative Atomic Mass: Defined as the average mass of the atom as compared to 1/12th the mass of one carbon-12 atom.

5. Molecules

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms chemically bonded together. It is the smallest particle of a substance capable of independent existence and retaining all properties of the substance.

A. Molecules of Elements

Constituted by the same type of atoms. The number of atoms in a molecule is its Atomicity.

- Monoatomic: Argon (Ar), Helium (He).

- Diatomic: Oxygen (O2), Hydrogen (H2), Chlorine (Cl2).

- Tetra-atomic: Phosphorus (P4).

- Poly-atomic: Sulphur (S8).

B. Molecules of Compounds

Atoms of different elements join together in definite proportions.

- Water (H2O): Ratio by mass 1:8.

- Ammonia (NH3): Ratio by mass 14:3.

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2): Ratio by mass 3:8.

6. Ions and Valency

Ions

Charged species found in compounds containing metals and non-metals.

- Anion: Negatively charged ion (e.g., Chloride Cl-).

- Cation: Positively charged ion (e.g., Sodium Na+).

- Polyatomic Ion: A group of atoms carrying a net charge (e.g., Ammonium NH4+, Sulphate SO42-).

Valency

Valency is the combining power or capacity of an element. It determines how atoms of one element combine with atoms of another. It can be visualized using an "octopus" analogy (arms representing combining capacity).

7. Writing Chemical Formulae

A chemical formula is a symbolic representation of a compound's composition. To write them, one must know the symbols and valency of the elements.

Rules:

- The valencies or charges on the ion must balance.

- If a metal is present, it is written first (on the left). Example: CaO, NaCl, CuO.

- If a polyatomic ion is used, it is enclosed in brackets before writing the subscript number. Example: Mg(OH)2. Brackets are not needed if the number is 1 (e.g., NaOH).

Method (Criss-Cross):

Write the constituent elements and their valencies below them, then crossover the valencies.

- Hydrogen Chloride: H (valency 1), Cl (valency 1) → Formula: HCl

- Hydrogen Sulphide: H (valency 1), S (valency 2) → Formula: H2S

- Magnesium Chloride: Mg (charge +2), Cl (charge -1) → Formula: MgCl2

- Aluminium Oxide: Al (charge +3), O (charge -2) → Formula: Al2O3

- Calcium Oxide: Ca (valency 2), O (valency 2) → Simplified Formula: CaO

8. Molecular Mass and Formula Unit Mass

Molecular Mass

The sum of the atomic masses of all atoms in a molecule. It is the relative mass of a molecule expressed in atomic mass units (u).

Example (H2O):

Atomic mass of H = 1u, O = 16u.

Calculation: 2 × 1 + 1 × 16 = 18 u.

Formula Unit Mass

This term is used for substances whose constituent particles are ions (like NaCl). It is calculated exactly like molecular mass.

Example (CaCl2):

Atomic mass of Ca = 40u, Cl = 35.5u.

Calculation: 40 + (2 × 35.5) = 40 + 71 = 111 u.