Quick Navigation:

| | |

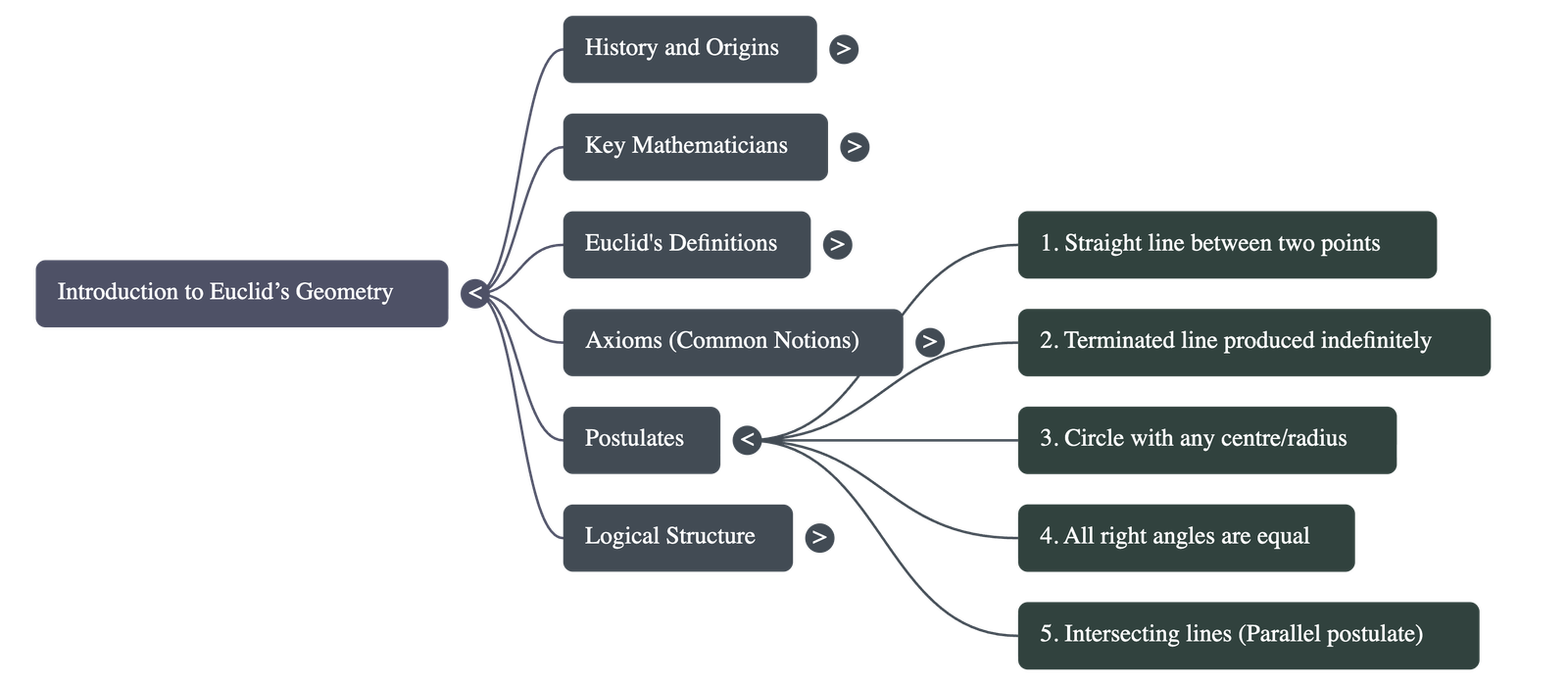

INTRODUCTION TO EUCLID’S GEOMETRY

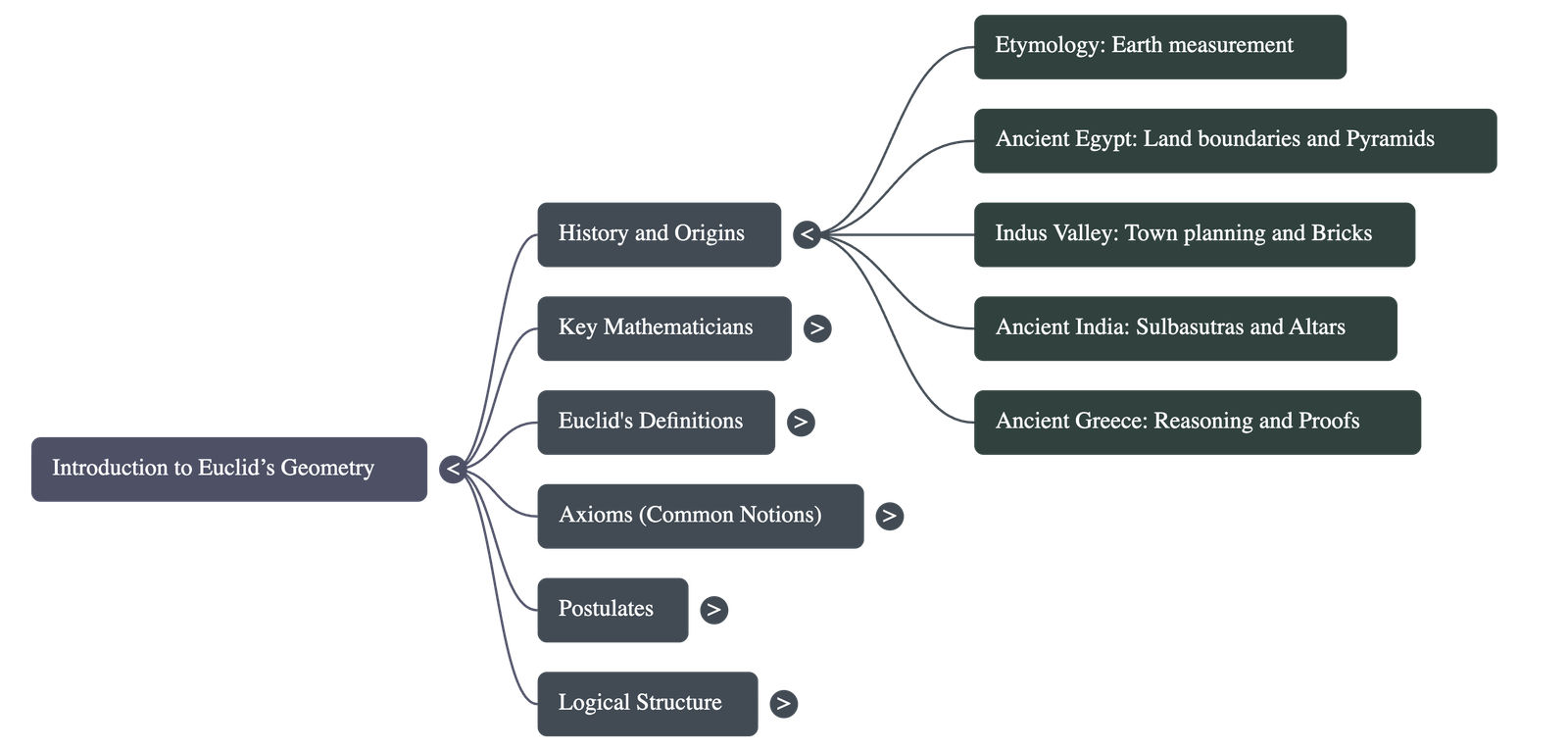

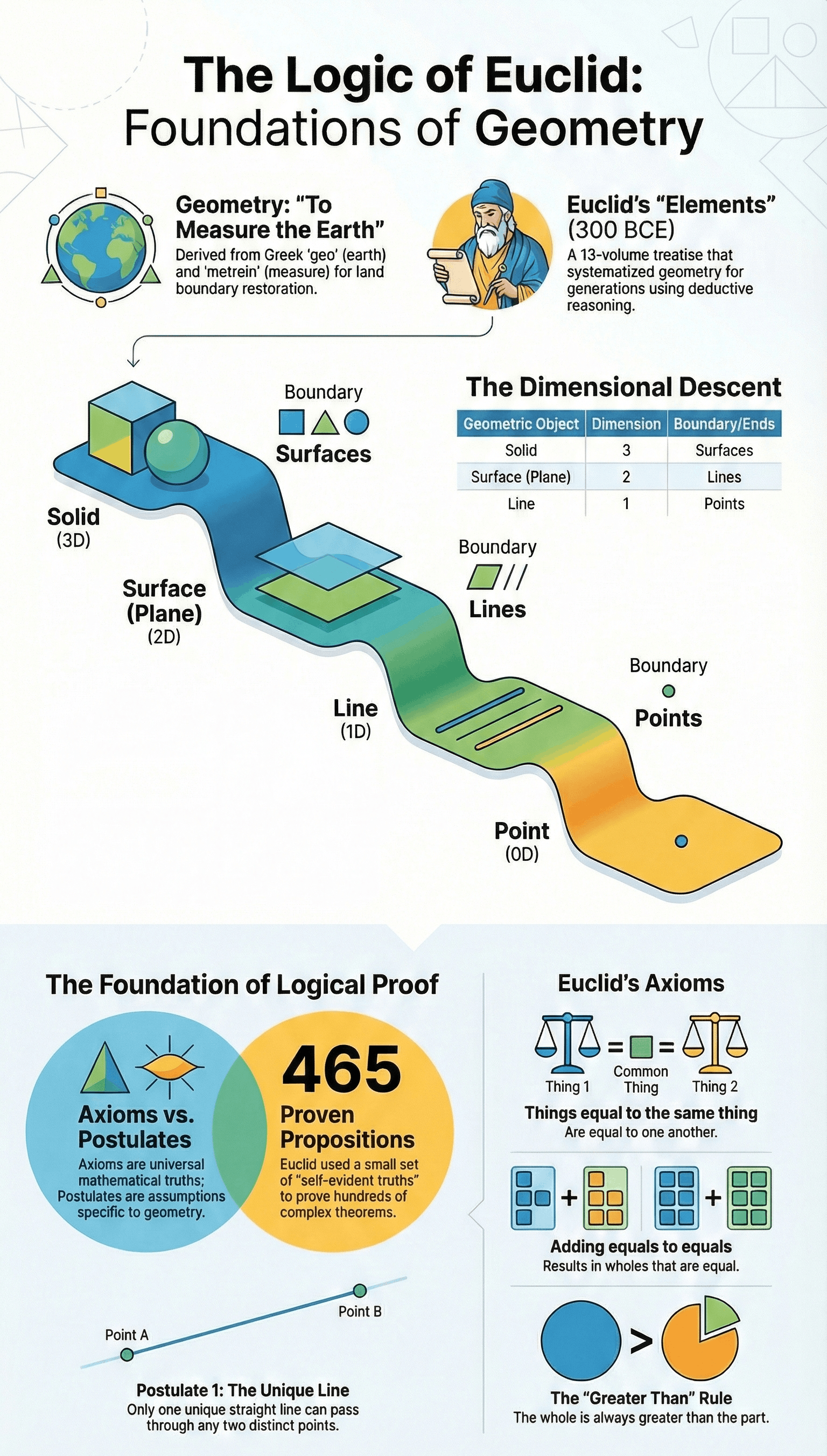

1. Historical Origins of Geometry

- The term geometry originates from the Greek words "geo" (earth) and "metrein" (to measure), suggesting its roots in land measurement.

- Ancient civilizations including Egypt, Babylonia, China, India, and Greece developed geometry to solve practical problems like redrawing field boundaries after floods, constructing granaries, and building pyramids.

- In the Indus Valley Civilisation, cities were highly planned with parallel roads and drainage systems. Bricks used for construction followed a specific ratio of 4:2:1 for length, breadth, and thickness.

- In ancient India, the Sulbasutras served as manuals for geometrical constructions, particularly for Vedic altars. The Sriyantra, mentioned in the Atharvaveda, is a complex arrangement of nine interwoven isosceles triangles.

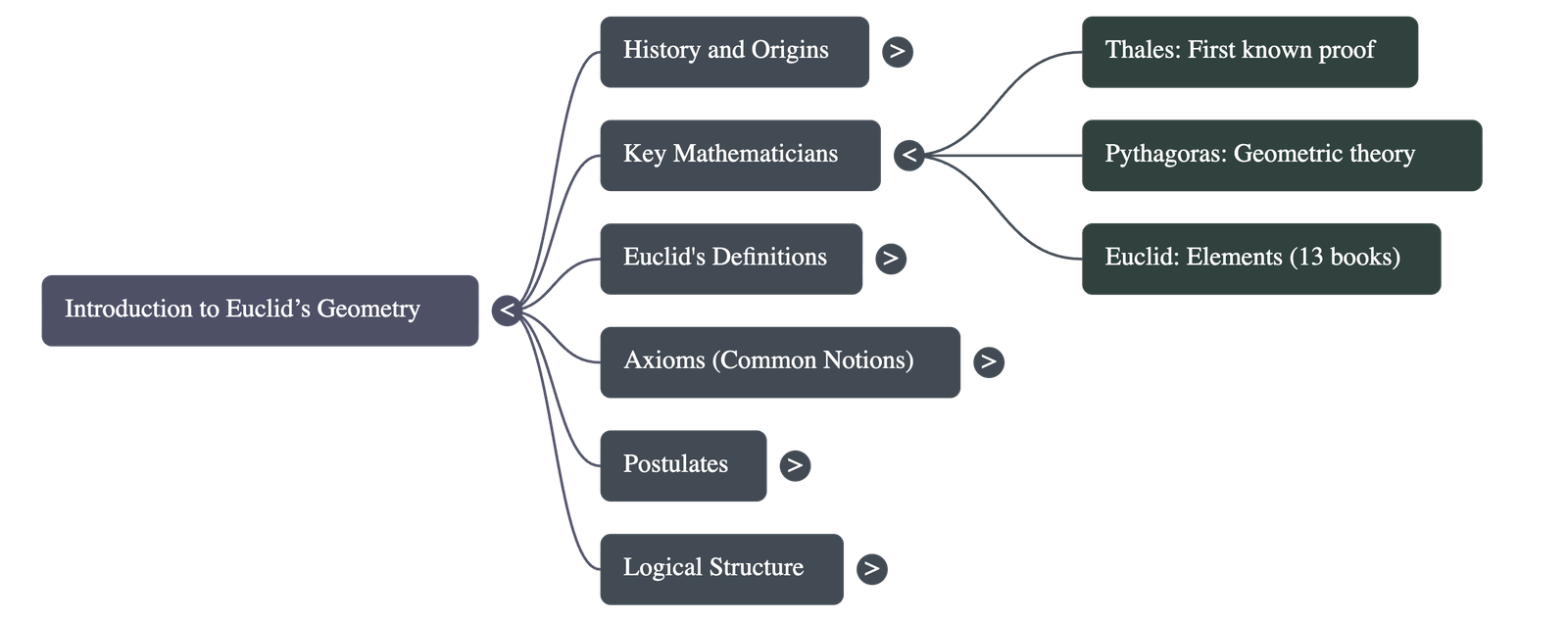

2. The Greek Contribution and Euclid

- While early geometry was practical, the Greeks emphasized deductive reasoning to establish the truth of mathematical statements.

- Thales is credited with the first known proof: that a circle is bisected by its diameter. His pupil Pythagoras further developed geometric theory.

- Euclid, a teacher in Alexandria, compiled all known mathematical knowledge into a famous treatise called "Elements," divided into thirteen chapters or "books."

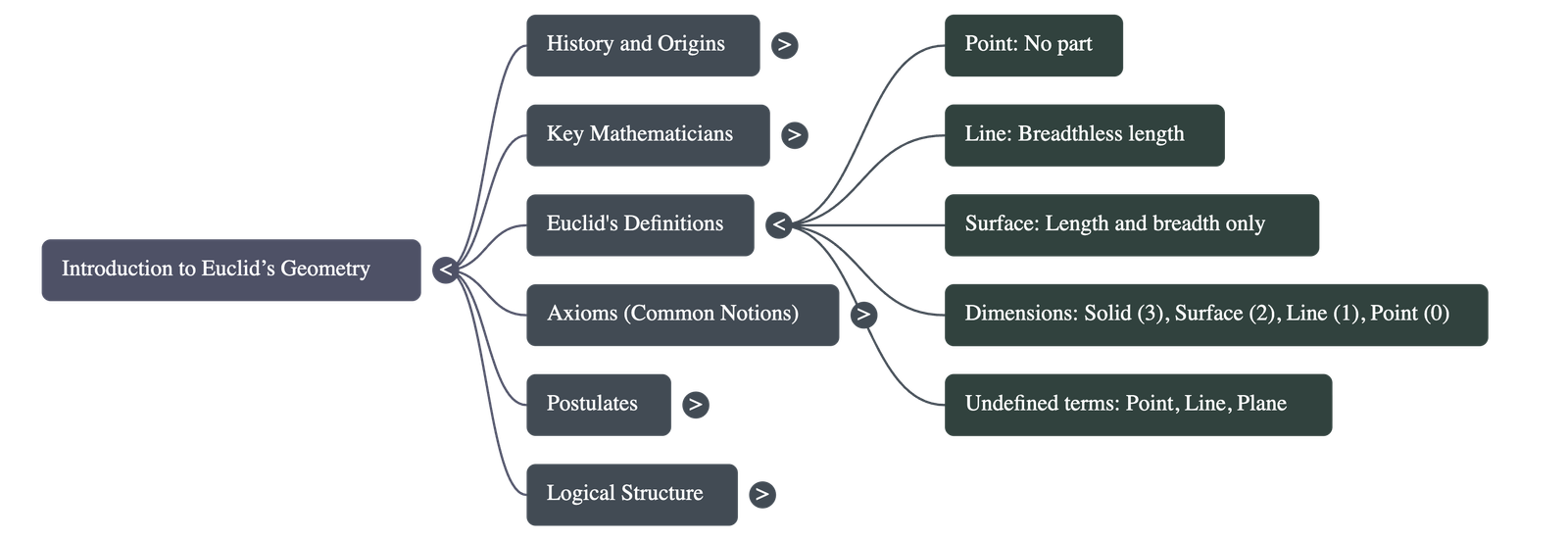

3. Definitions and Undefined Terms

- Euclid began his work with 23 definitions, such as:

- A point has no part.

- A line is breadthless length.

- A surface has length and breadth only.

- Modern mathematicians recognize that defining every term leads to an infinite chain. Therefore, in modern geometry, point, line, and plane are treated as undefined terms.

- A solid has three dimensions, a surface has two, a line has one, and a point has zero dimensions.

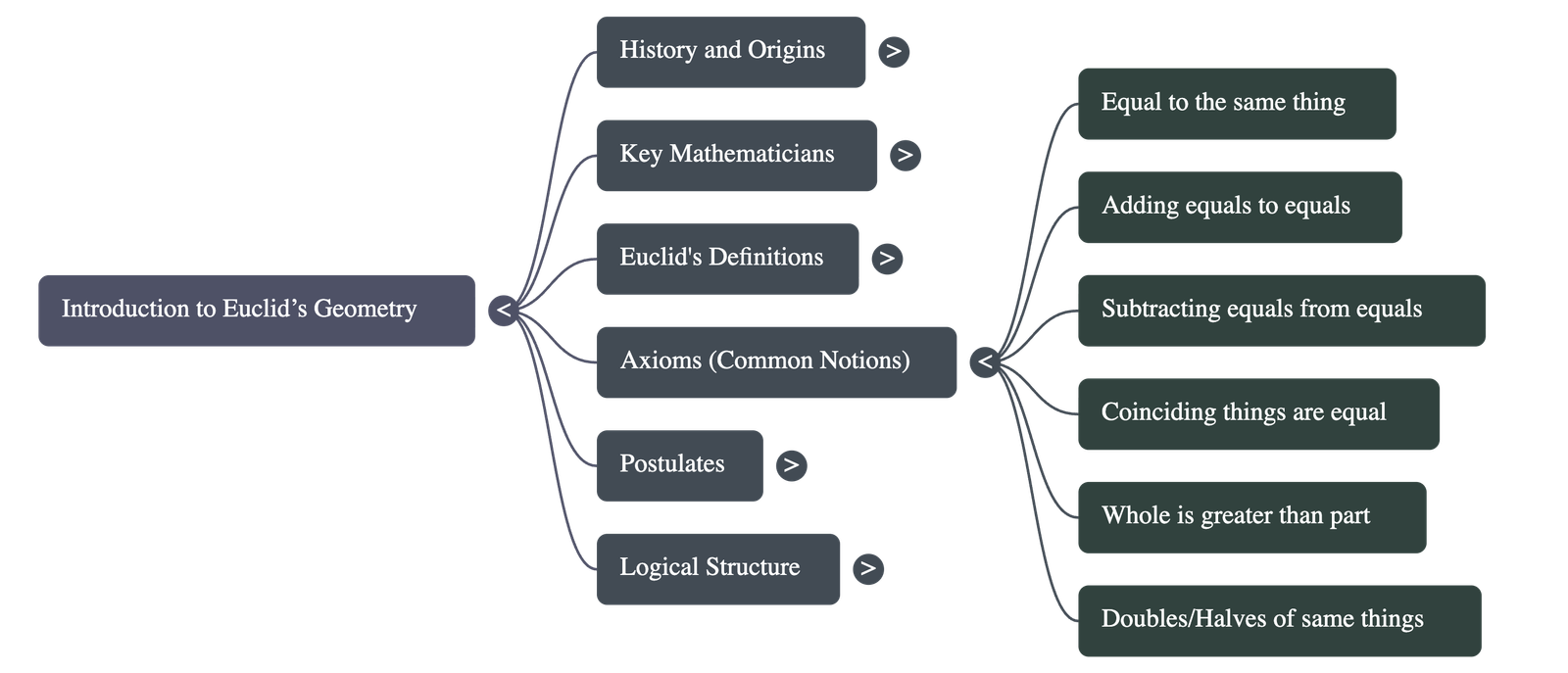

4. Euclid’s Axioms (Common Notions)

Axioms are assumptions used throughout mathematics that are accepted as universal truths without proof. Key axioms include:

- Things which are equal to the same thing are equal to one another.

- If equals are added to equals, the wholes are equal.

- If equals are subtracted from equals, the remainders are equal.

- Things which coincide with one another are equal to one another.

- The whole is greater than the part.

- Things which are double of the same things are equal to one another.

- Things which are halves of the same things are equal to one another.

5. Euclid’s Five Postulates

Postulates are assumptions specific to the field of geometry:

- Postulate 1: A straight line may be drawn from any one point to any other point. (Modern addition: This line is unique).

- Postulate 2: A terminated line (line segment) can be produced indefinitely.

- Postulate 3: A circle can be drawn with any centre and any radius.

- Postulate 4: All right angles are equal to one another.

- Postulate 5: If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the lines will eventually meet on that side if produced indefinitely.

6. Theorems and Deductive Reasoning

- Using axioms, postulates, and definitions, Euclid proved 465 propositions or theorems.

- A system of axioms is considered consistent if it is impossible to deduce a statement that contradicts any other axiom or previously proved truth.

- Theorem Example: Two distinct lines cannot have more than one point in common. If they had two, it would contradict the axiom that only one line passes through two distinct points.

Quick Navigation:

| | |

1 / 1

Quick Navigation:

| | |