Quick Navigation:

| | |

The Age of Industrialisation

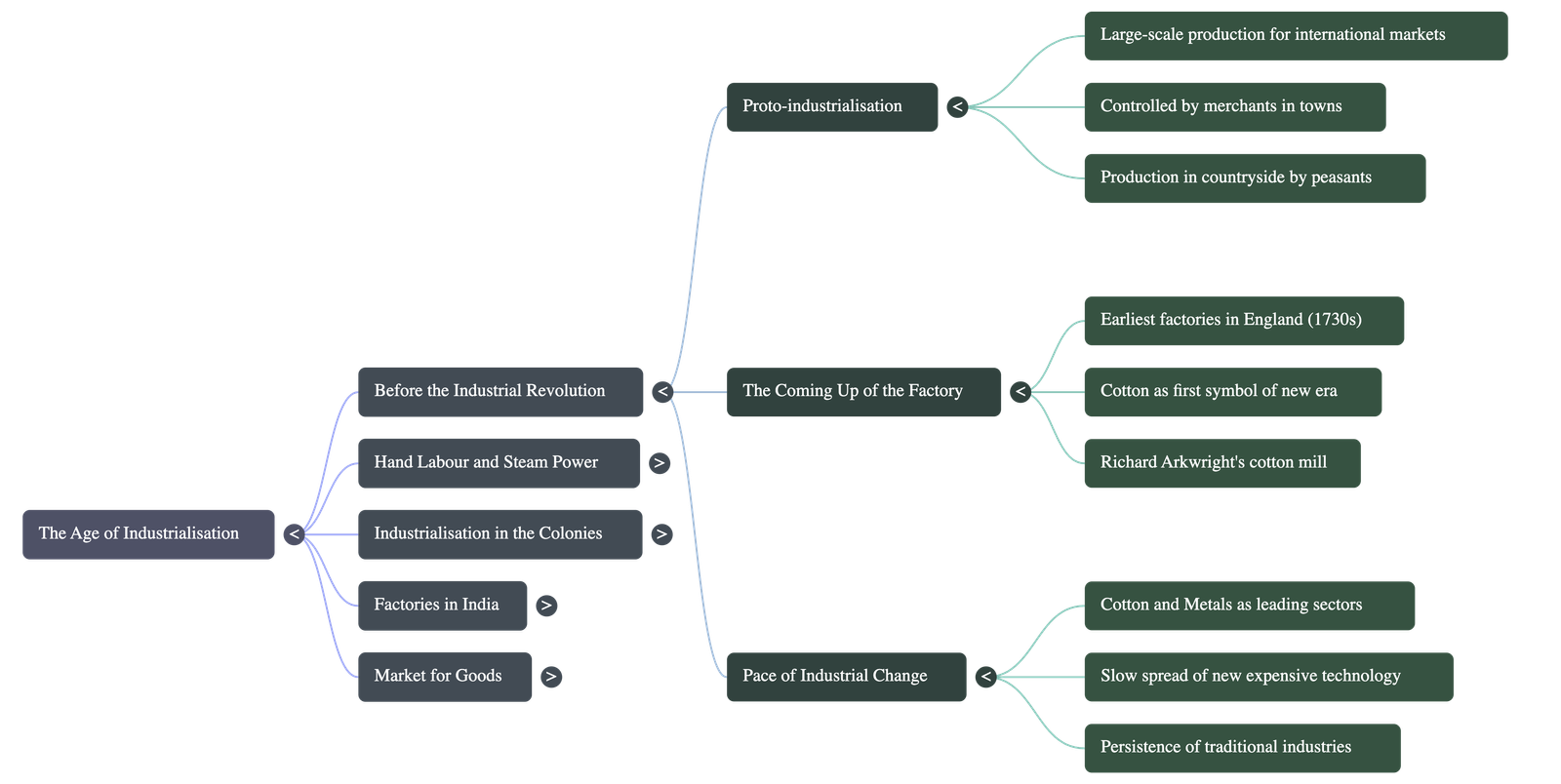

Introduction: The chapter begins by contrasting the glorification of machines and technology in early 20th-century popular culture (like the "Dawn of the Century" music book) with the complex reality of industrialisation. It explores the history of industrial change in Britain and India.

1. Before the Industrial Revolution

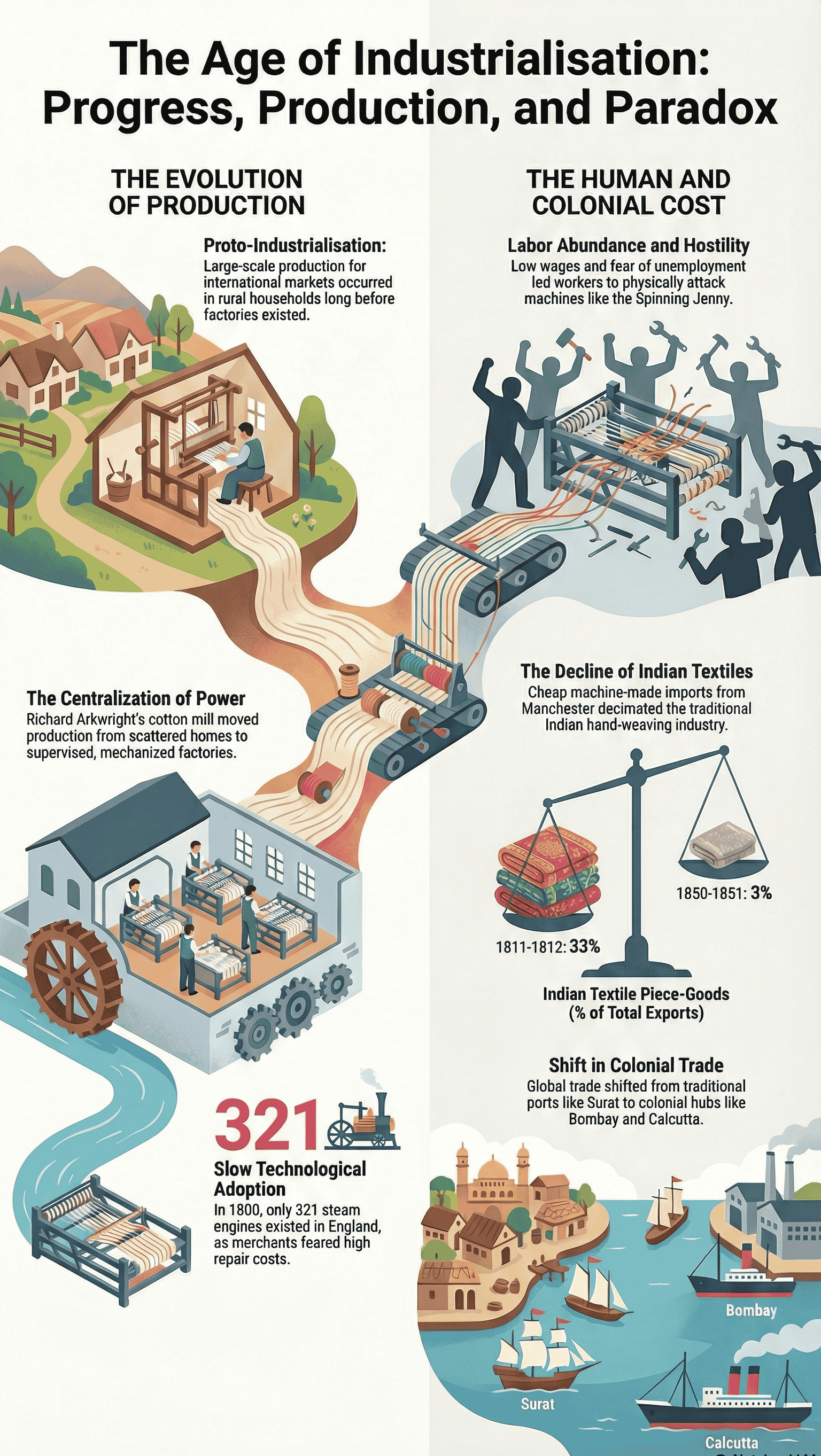

- Proto-industrialisation: Even before factories began to dot the landscape, there was large-scale industrial production for an international market. Historians call this phase "proto-industrialisation."

- Merchants and the Countryside: In the 17th and 18th centuries, merchants moved to the countryside because urban guilds were too powerful. Guilds restricted entry, regulated prices, and maintained monopolies.

- Relationship with Peasants: Poor peasants and cottagers, who had lost their common lands due to enclosures, eagerly accepted advances from merchants. This system allowed them to stay in the countryside and cultivate small plots while weaving for merchants.

- The Commercial Network: London became a "finishing centre." A merchant clothier purchased wool from a stapler, took it to spinners, then to weavers, fullers, and dyers before export.

1.1 The Coming Up of the Factory

- The Symbol of the Era: Cotton was the first symbol of the new industrial era. Imports of raw cotton to Britain soared from 2.5 million pounds in 1760 to 22 million pounds by 1787.

- Technological Inventions: Inventions in carding, twisting, spinning, and rolling enhanced output per worker.

- Richard Arkwright: He created the cotton mill, bringing processes under one roof. This allowed for better supervision, quality control, and labor regulation compared to the dispersed countryside production.

1.2 The Pace of Industrial Change

- Leading Sectors: Cotton was the leading sector up to the 1840s, followed by the iron and steel industry due to the expansion of railways.

- Persistence of Tradition: New industries could not easily displace traditional ones. Less than 20% of the workforce was in technologically advanced sectors even by the late 19th century.

- Ordinary Innovations: Growth in non-mechanised sectors (food processing, building, pottery) came from small, ordinary innovations.

- Slow Technological Adoption: Industrialists were cautious about new technology. For example, James Watt’s improved steam engine found few buyers for years. Steam engines were not widely used in industries other than mining and cotton textiles until much later.

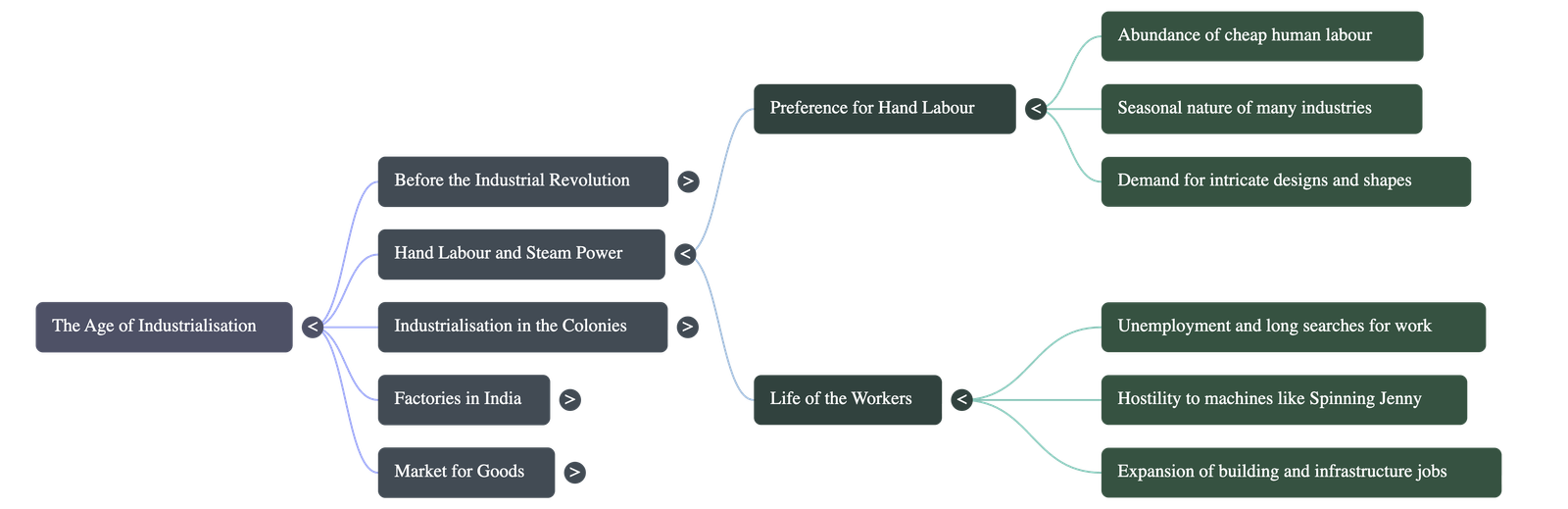

2. Hand Labour and Steam Power

- Abundance of Labour: In Victorian Britain, there was no shortage of human labor, so wages were low. Industrialists preferred hand labor over expensive machines that required large capital investment.

- Seasonal Demand: Industries like gas works, breweries, and bookbinding had seasonal fluctuations and preferred employing hand labor for specific periods rather than investing in machines.

- Class Preferences: The aristocracy and bourgeoisie preferred handmade goods because they symbolised refinement and class. Machine-made goods were primarily for export to the colonies.

2.1 Life of the Workers

- Migration and Unemployment: Hundreds tramped to cities for work, but finding a job depended on social networks (kinship/friendship). Many spent nights in shelters, under bridges, or in casual wards.

- Seasonality: Workers faced prolonged periods without work. After the busy season, the poor were often on the streets again.

- Real Wages: While wages rose somewhat, the "real value" often fell due to inflation (e.g., during the Napoleonic Wars) and the irregularity of employment.

- Hostility to Technology: Fear of unemployment made workers hostile to new technology. Women in the woollen industry attacked the Spinning Jenny because it threatened their hand-spinning jobs.

- Infrastructure Boom: After the 1840s, employment opportunities expanded due to building activities (roads, railways, tunnels, sewers).

3. Industrialisation in the Colonies: India

- The Age of Indian Textiles: Before machine industries, Indian silk and cotton dominated international markets. A vibrant network of Indian merchants and bankers controlled the trade through ports like Surat and Masulipatam.

- Decline of Old Ports: With the entry of European companies, old ports (Surat, Hoogly) declined, and new colonial ports (Bombay, Calcutta) grew. Trade came to be controlled by European companies using European ships.

3.2 What Happened to Weavers?

- Establishment of Control: Once the East India Company gained political power, it asserted a monopoly on trade and eliminated competition from other European powers and local traders.

- The Gomastha: The Company appointed paid servants called gomasthas to supervise weavers, collect supplies, and examine cloth quality. They were often outsiders who acted arrogantly and punished weavers.

- System of Advances: Weavers were given loans (advances) to buy raw materials. This tied them to the Company, preventing them from selling to other buyers. Weavers lost their bargaining power and became dependent on the Company.

- Result: Clashes between weavers and gomasthas became common. Many weavers deserted their villages or closed down their workshops.

3.3 Manchester Comes to India

- Decline of Exports: By the 19th century, Indian textile exports declined dramatically. British industrialists pressured their government to impose import duties on Indian goods and force the East India Company to sell British goods in India.

- Flooding the Market: By 1850, machine-made Manchester goods flooded the Indian market. They were so cheap that Indian weavers could not compete.

- Raw Material Crisis: During the American Civil War, Britain turned to India for raw cotton. Prices shot up, starving Indian weavers of affordable raw material.

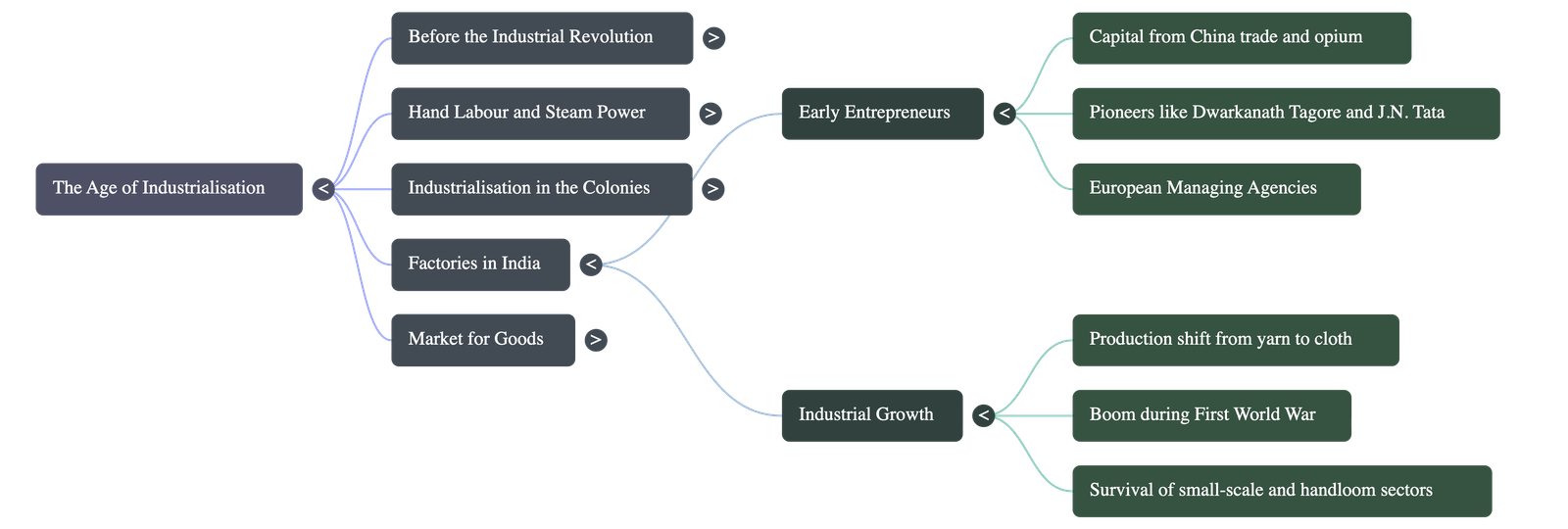

4. Factories Come Up in India

The first cotton mill in Bombay came up in 1854. Jute mills followed in Bengal (1855), and mills were established in Kanpur, Ahmedabad, and Madras by the 1870s.

4.1 The Early Entrepreneurs

- Trade with China: Many early Indian industrialists (e.g., Dwarkanath Tagore, Dinshaw Petit, Jamsetjee Nusserwanjee Tata) accumulated initial wealth through the China trade (opium and tea) and raw cotton shipments.

- European Control: Indian merchants were eventually barred from trading in manufactured goods with Europe. European Managing Agencies (e.g., Bird Heiglers & Co.) controlled a large sector of Indian industries, making investment decisions while Indians provided capital.

4.2 Where Did the Workers Come From?

- Village Links: Workers came from neighboring districts (e.g., Ratnagiri to Bombay). They maintained close links with their villages, returning for harvests.

- The Jobber: Recruitment was done through a "jobber," usually an old and trusted worker. The jobber got people from his village, ensured jobs, and helped settle them, eventually becoming a person of authority and power who demanded money for favors.

5. The Peculiarities of Industrial Growth

- Avoiding Competition: Early Indian cotton mills avoided competing with Manchester cloth by producing coarse cotton yarn (thread) rather than fabric. This yarn was used by Indian handloom weavers or exported to China.

- Swadeshi Movement: Nationalists mobilised people to boycott foreign cloth, boosting Indian industry.

- First World War Boom: The war was a turning point. Manchester imports declined as British mills were busy with war production. Indian factories were called upon to supply war needs (jute bags, uniforms), leading to a boom in industrial production and the consolidation of Indian industries.

5.1 Small-scale Industries Predominate

- Dominance of Small Sector: Large factories were a small segment of the economy. Most production occurred in small workshops and households.

- Survival of Handloom: Handloom cloth production expanded in the 20th century. This was partly due to technological adoption, such as the fly shuttle, which increased productivity.

- Coarse vs. Fine Cloth: Weavers of coarse cloth suffered during famines (as the poor could not buy), while weavers of fine varieties (like Banarasi or Baluchari saris) had a more stable market among the well-to-do.

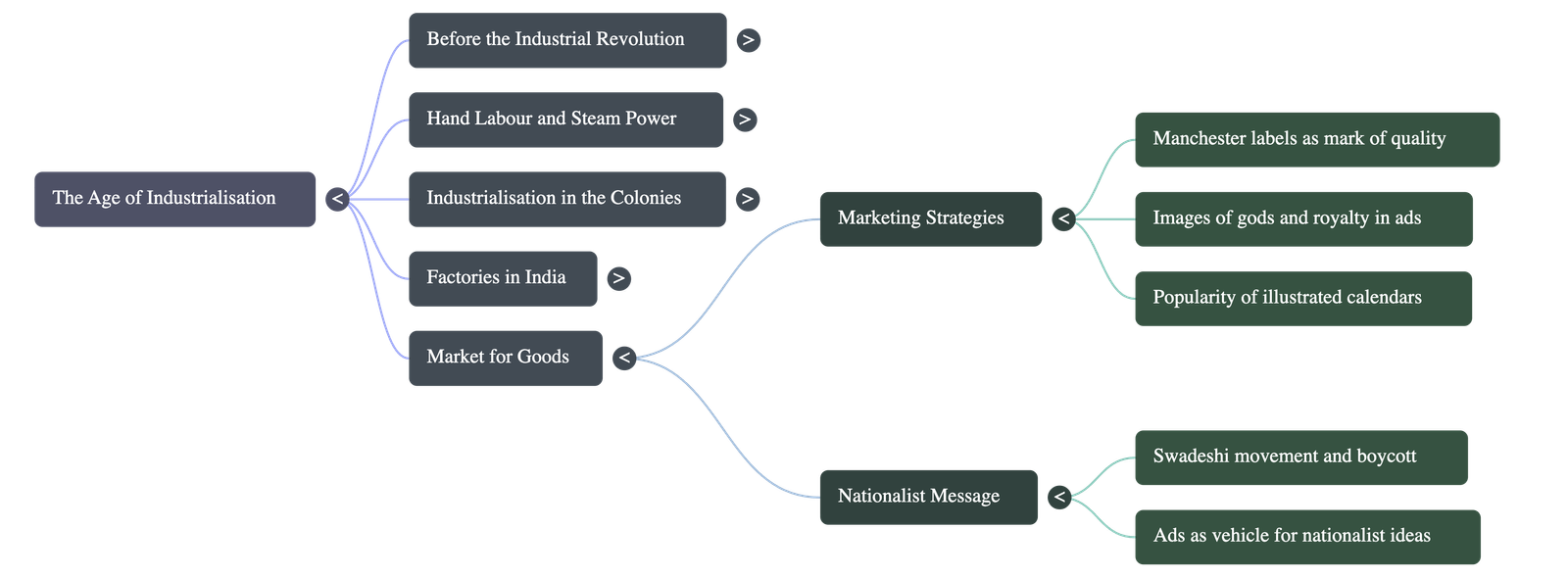

6. Market for Goods

- Creating Consumers: Manufacturers used advertisements to create new needs and make products appear desirable.

- Labels: Manchester industrialists put "MADE IN MANCHESTER" labels on cloth bundles to signify quality. These labels often carried beautiful illustrations.

- Religious Imagery: Images of Indian gods and goddesses (Krishna, Saraswati, Lakshmi) were used on labels and calendars to give divine approval to foreign goods and make them feel familiar to Indian buyers.

- Calendars: Calendars were a popular advertising medium because they were used even by the illiterate and hung in homes and tea shops, ensuring daily visibility of the brand.

- Nationalist Advertising: Indian manufacturers used advertisements to spread the message of Swadeshi: "If you care for the nation, then buy products that Indians produce."

Quick Navigation:

| | |

1 / 1

Quick Navigation:

| | |