Quick Navigation:

| | |

The Rise of Nationalism in Europe

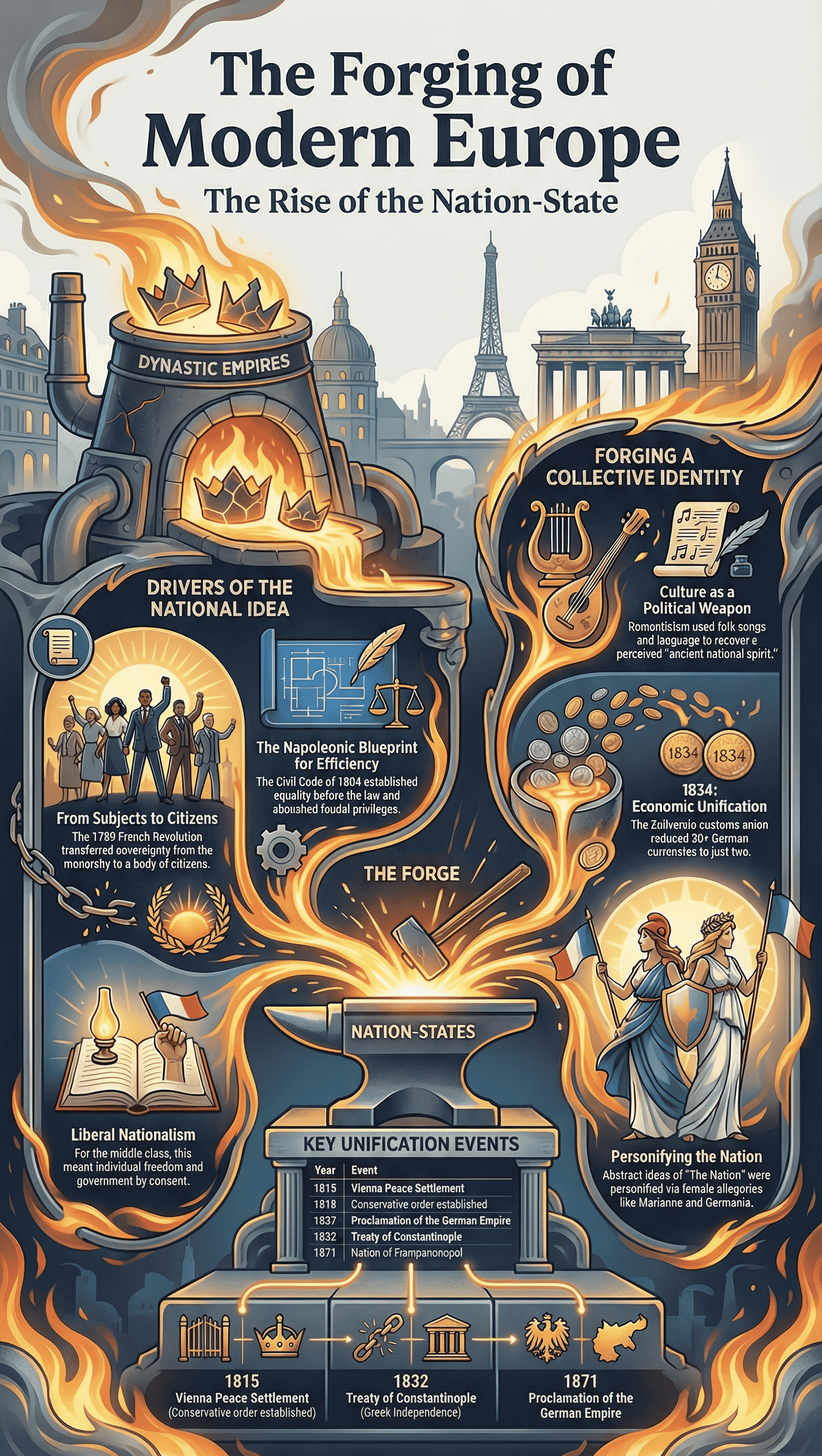

Introduction: The Vision of a New World

- Frédéric Sorrieu’s Utopia (1848): A French artist visualized a world of "democratic and social Republics." His prints depicted peoples of Europe and America marching to offer homage to the Statue of Liberty, symbolizing the end of absolutist institutions.

- The Nation-State: The 19th century witnessed the emergence of the nation-state, replacing multi-national dynastic empires. This concept involved a centralized power exercising sovereign control over a defined territory, where citizens shared a common identity and history.

- Ernst Renan’s Definition: In his essay "What is a Nation?", Renan defined a nation not by race or religion, but as the culmination of a long past of endeavors, sacrifice, and devotion—a "large-scale solidarity."

1. The French Revolution and the Idea of the Nation

- First Expression of Nationalism (1789): The revolution transferred sovereignty from the monarchy to the body of French citizens.

- Creating Collective Identity: Revolutionaries introduced ideas like la patrie (the fatherland) and le citoyen (the citizen). A new tricolour flag replaced the royal standard, and the Estates General was renamed the National Assembly.

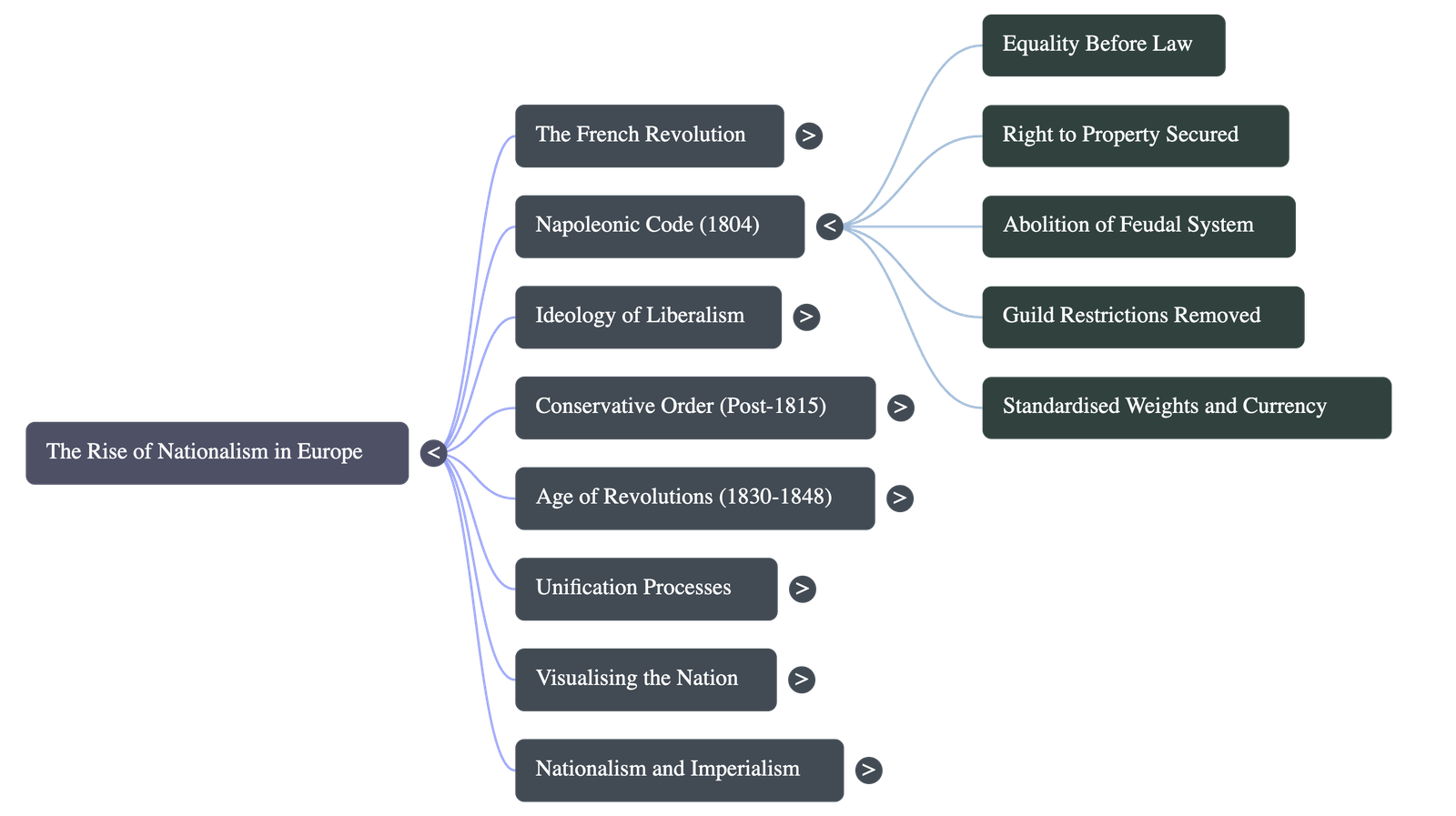

- Administrative Centralization: A centralized administrative system formulated uniform laws. Internal customs duties were abolished, and a uniform system of weights and measures was adopted. French became the common language, suppressing regional dialects.

- Napoleon’s Reforms (The Civil Code of 1804): Also known as the Napoleonic Code, it abolished privileges based on birth, established equality before the law, and secured the right to property.

- Mixed Reactions: While French armies were initially welcomed as harbingers of liberty in places like Holland and Switzerland, hostility grew due to increased taxation, censorship, and forced conscription into the French army.

2. The Making of Nationalism in Europe

Mid-18th-century Europe had no "nation-states" as we know them; it was a patchwork of kingdoms and duchies with diverse ethnic groups.

- Aristocracy vs. Peasantry: Landed aristocracy was the dominant class socially and politically, though small in number. The majority of the population was peasantry (tenants in the West, serfs in the East).

- The New Middle Class: Industrialization led to the rise of commercial classes—industrialists, businessmen, and professionals. It was among this educated, liberal middle class that ideas of national unity gained popularity.

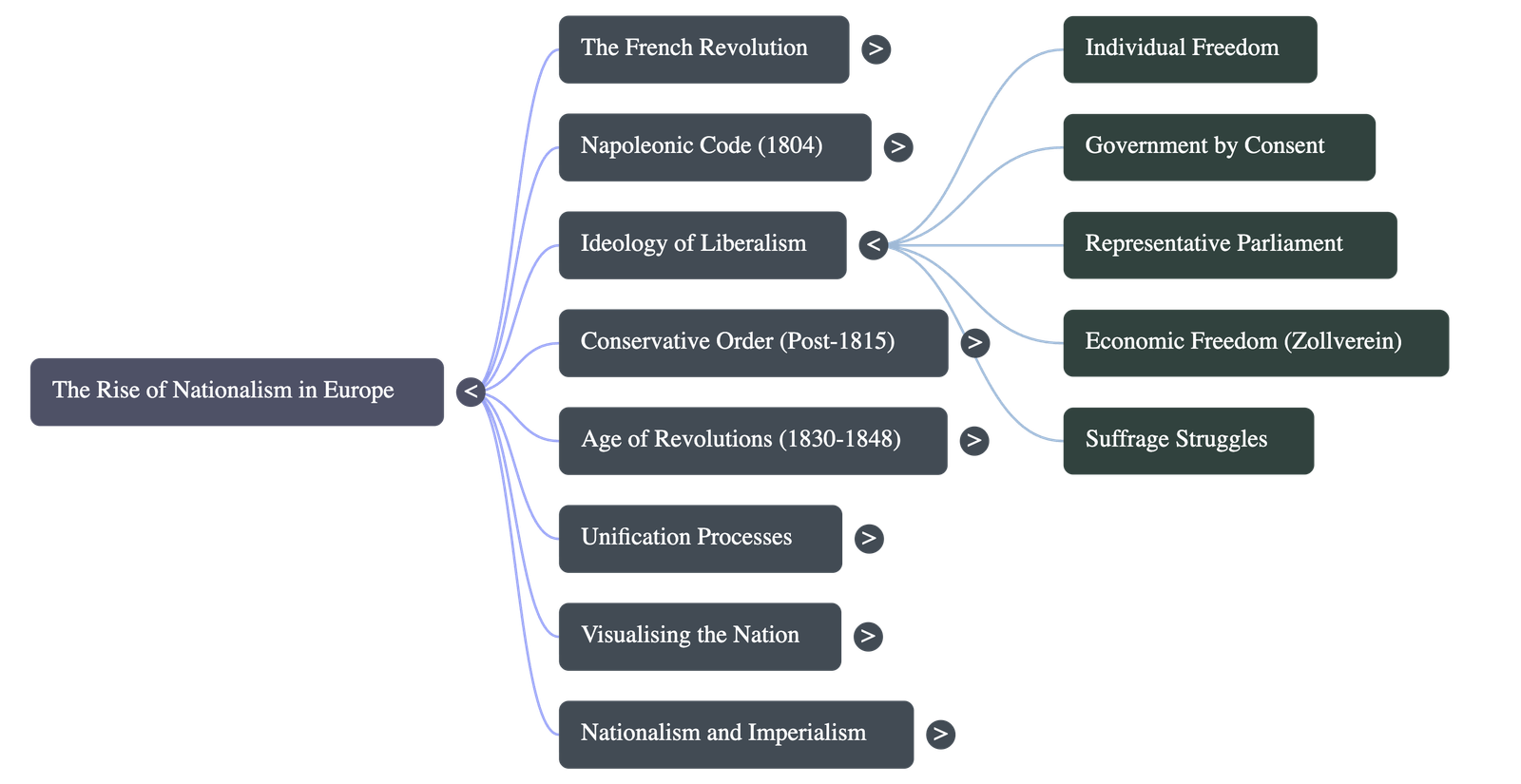

- Liberal Nationalism:

- Political: Stood for freedom of the individual, equality before the law, and government by consent. However, this did not necessarily mean universal suffrage (women and non-propertied men were often excluded).

- Economic: Stood for the freedom of markets and the abolition of state-imposed restrictions on the movement of goods.

- The Zollverein (1834): A customs union formed at the initiative of Prussia. It abolished tariff barriers and reduced the number of currencies from over thirty to two, binding Germany economically.

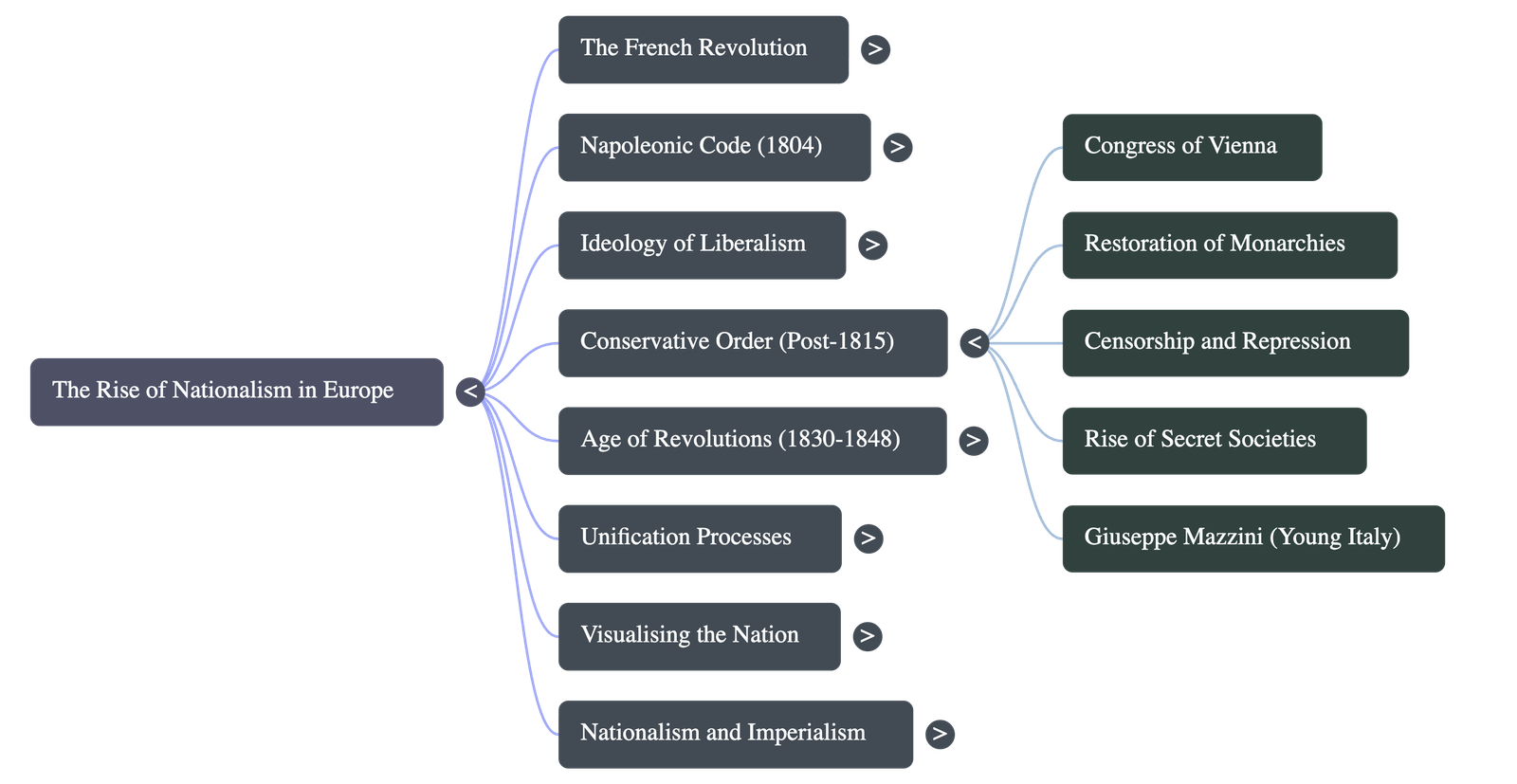

- A New Conservatism (1815): After Napoleon's defeat, European powers (Britain, Russia, Prussia, Austria) met at the Congress of Vienna, hosted by Duke Metternich. Their goal was to undo the changes of the Napoleonic wars and restore monarchies (e.g., the Bourbons in France).

- The Revolutionaries: Liberal-nationalists went underground to fight for liberty and oppose the autocratic regimes. Giuseppe Mazzini founded secret societies like "Young Italy" and "Young Europe," believing that God intended nations to be the natural units of mankind.

3. The Age of Revolutions (1830-1848)

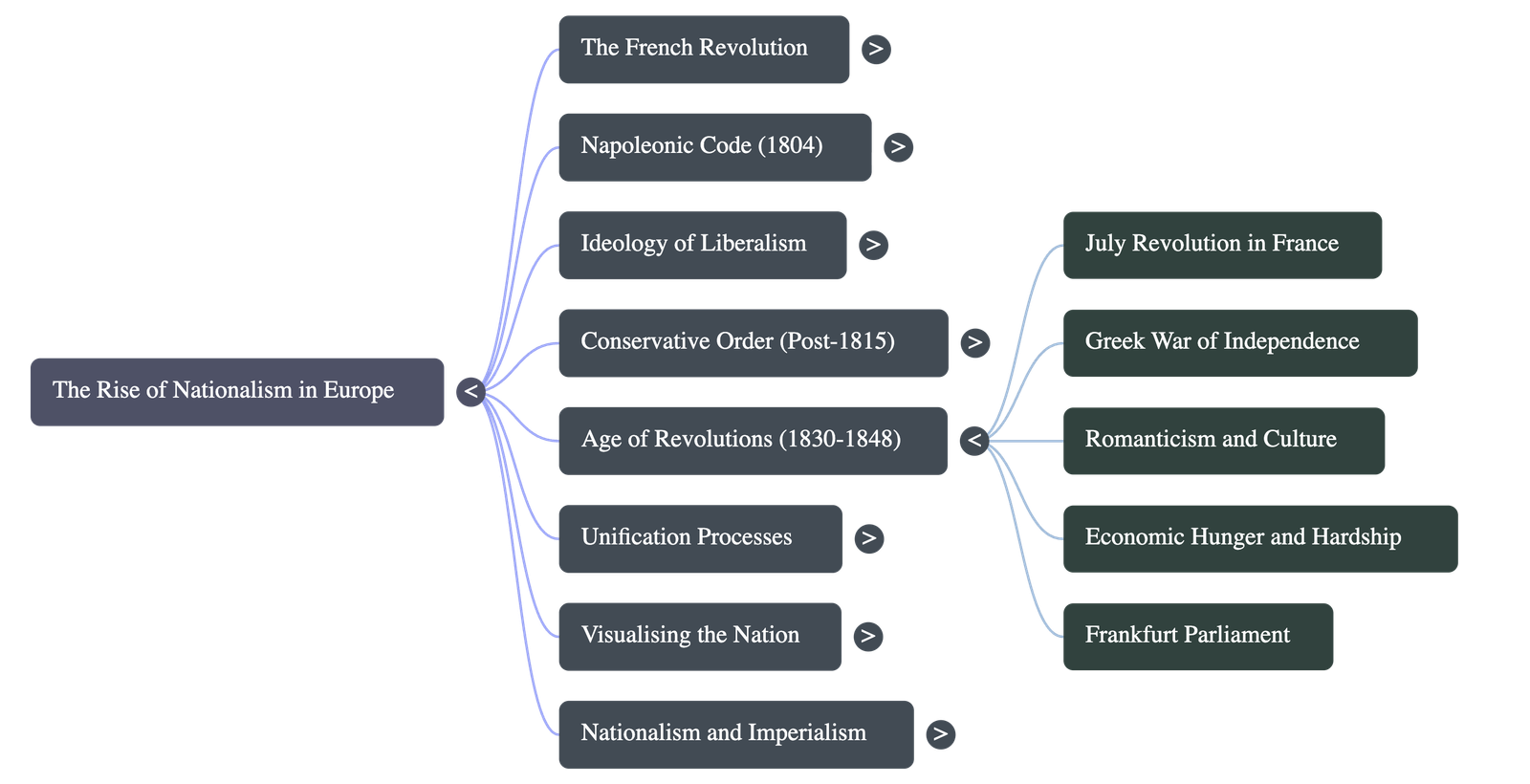

- July Revolution (1830): Bourbon kings were overthrown in France; a constitutional monarchy was installed under Louis Philippe. This sparked the independence of Belgium from the Netherlands.

- Greek War of Independence: A struggle against the Ottoman Empire beginning in 1821. Supported by West Europeans and artists (like Lord Byron), Greece was recognized as an independent nation by the Treaty of Constantinople (1832).

- The Role of Culture (Romanticism): A cultural movement that criticized reason and science, focusing instead on emotions and folklore.

- Volksgeist: Johann Gottfried Herder claimed true German culture was among the common people (das volk).

- Language as Resistance: In Poland, the use of Polish was used as a weapon of national resistance against Russian dominance.

- Grimm Brothers: Collected folktales to oppose French domination and create a German national identity.

- 1848: The Revolution of the Liberals:

- In France, food shortages and unemployment forced Louis Philippe to flee; a Republic was proclaimed with universal male suffrage.

- Frankfurt Parliament: In German regions, middle-class professionals voted for an all-German National Assembly. They drafted a constitution for a monarchy subject to parliament. King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia rejected it, and the assembly was disbanded by troops.

- Women’s Rights: Despite active participation, women were denied suffrage and were only allowed to observe the Frankfurt parliament from the visitors' gallery.

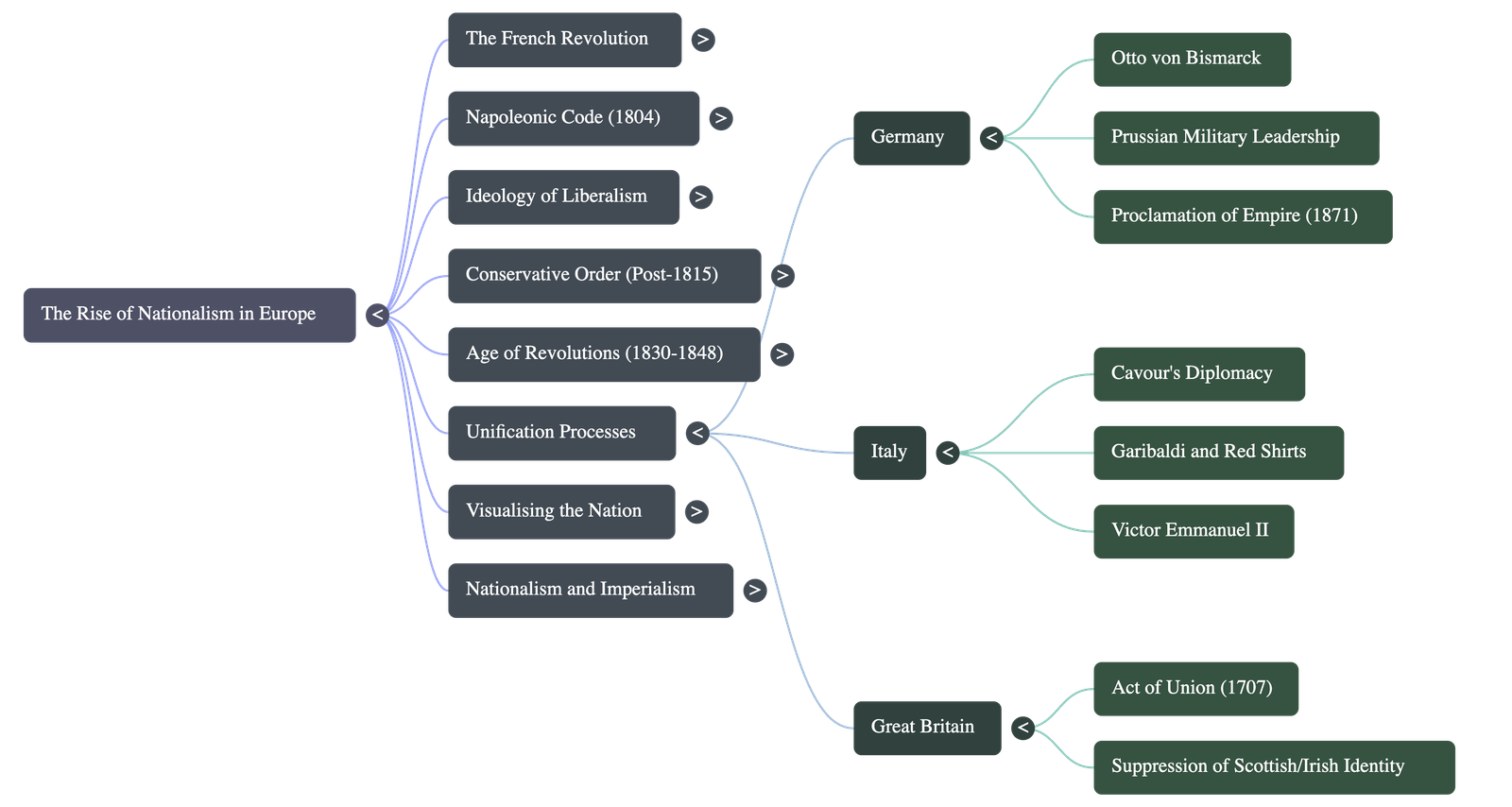

4. The Making of Germany and Italy

Germany

- Nationalist feelings were widespread but repressed by the monarchy and military.

- Prussia took the leadership of national unification.

- Otto von Bismarck was the architect, using the Prussian army and bureaucracy.

- Three wars over seven years (against Austria, Denmark, and France) ended in Prussian victory.

- In January 1871, Prussian King William I was proclaimed German Emperor in a ceremony at Versailles.

Italy

- Italy was fragmented into seven states; only Sardinia-Piedmont was ruled by an Italian princely house.

- Giuseppe Mazzini: Ideally sought a unitary Republic (Young Italy).

- Count Cavour: Chief Minister of Sardinia-Piedmont. Through a diplomatic alliance with France, he defeated Austrian forces in 1859.

- Giuseppe Garibaldi: Led armed volunteers (Red Shirts). In 1860, they marched into South Italy and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, winning peasant support.

- In 1861, Victor Emmanuel II was proclaimed king of united Italy.

The Strange Case of Britain

- The formation of the nation-state was a long process, not a sudden revolution.

- The English Parliament seized power from the monarchy in 1688.

- Act of Union (1707): United England and Scotland into the "United Kingdom of Great Britain," resulting in the suppression of Scottish culture and language.

- Ireland was forcibly incorporated into the UK in 1801 after the failure of Wolfe Tone’s revolt.

- A new "British nation" was forged through the propagation of English culture (Union Jack, God Save Our Noble King, English language).

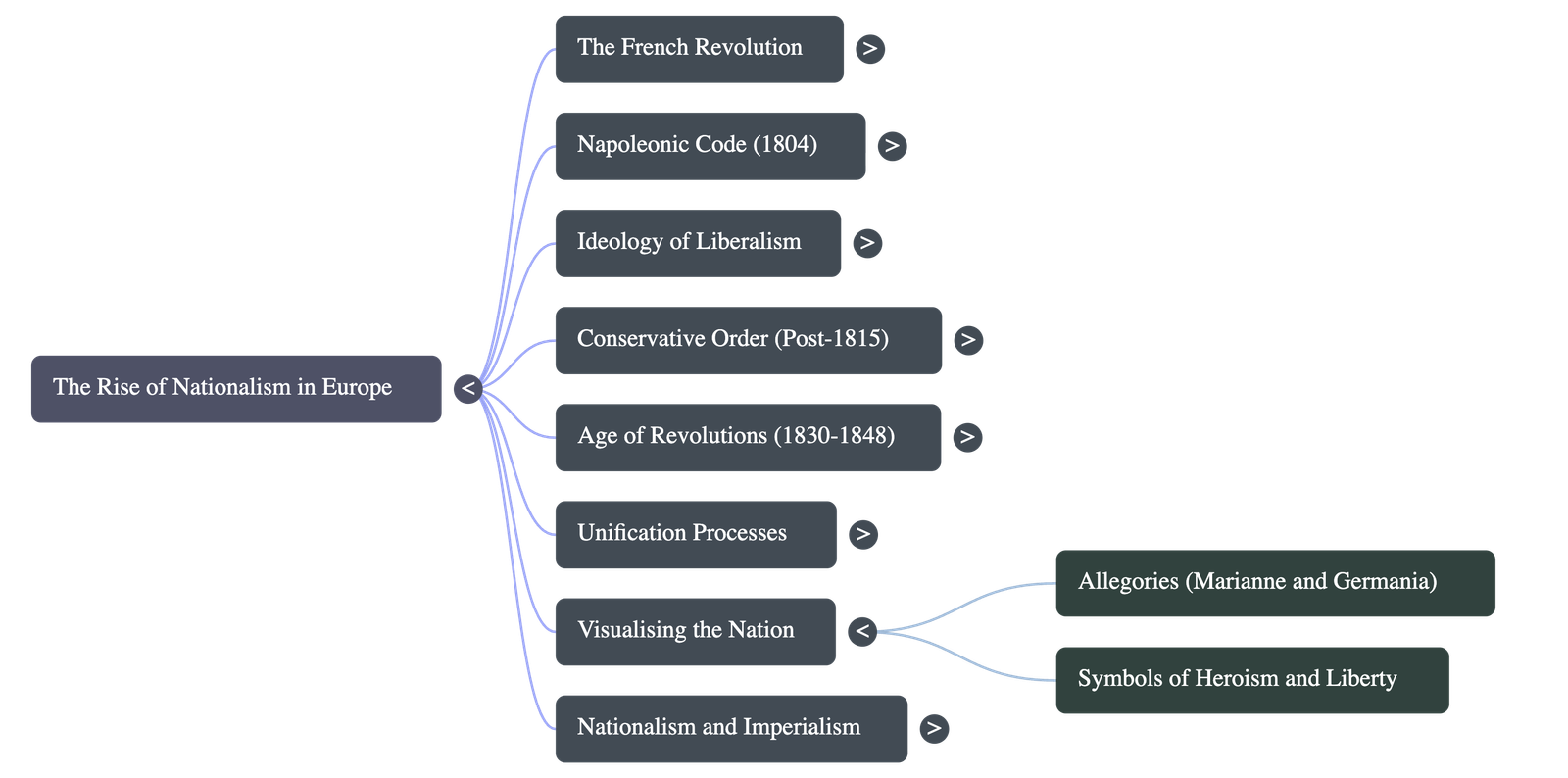

5. Visualising the Nation

Artists in the 18th and 19th centuries personified nations as female figures (Allegory).

- France (Marianne): Characterized by the red cap, the tricolour, and the cockade. Her statues were erected in public squares to symbolize national unity.

- Germany (Germania): Portrayed wearing a crown of oak leaves, as the German oak stands for heroism.

- Symbols:

- Broken chains: Being freed.

- Sword: Readiness to fight.

- Olive branch around sword: Willingness to make peace.

- Rays of the rising sun: Beginning of a new era.

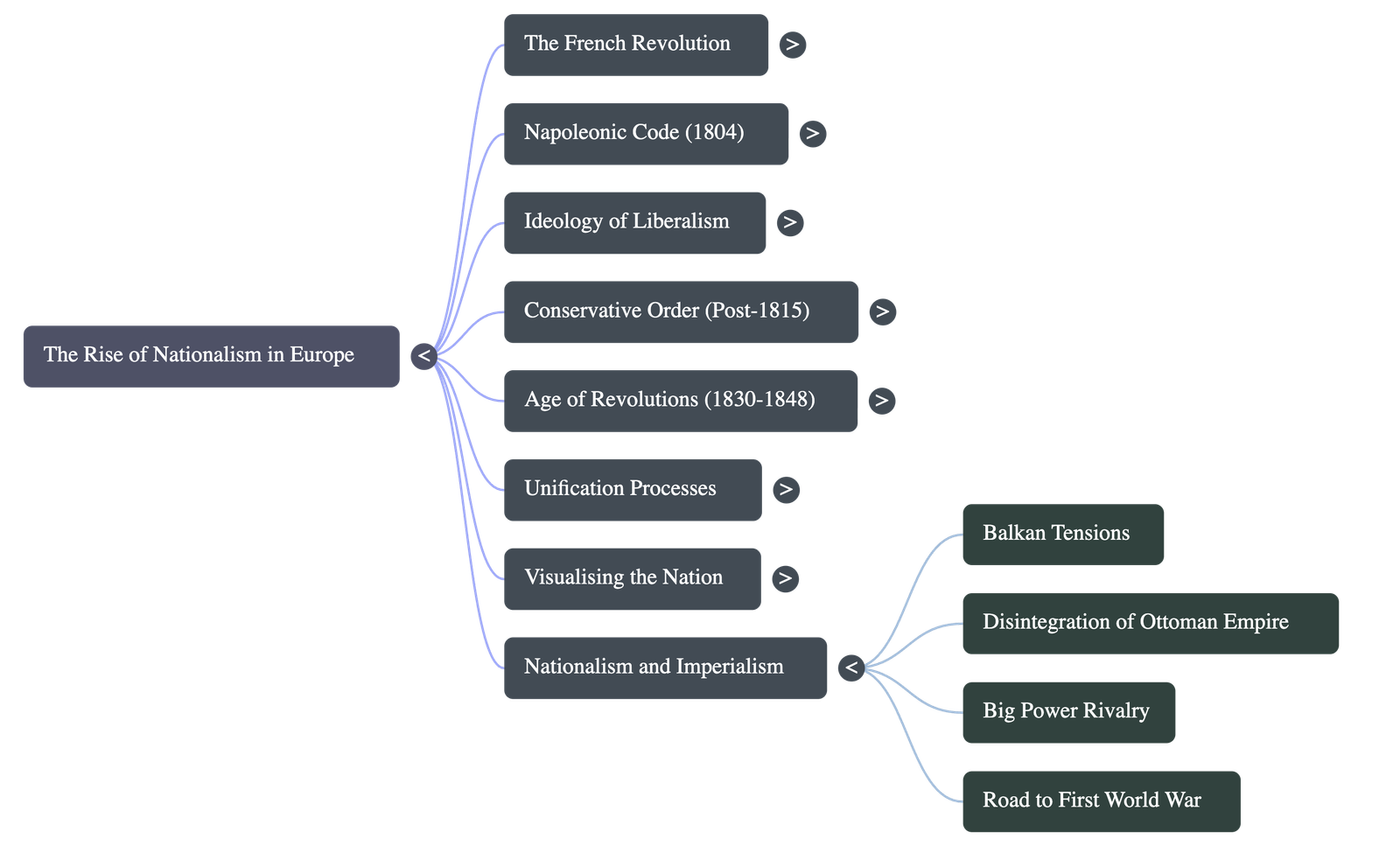

6. Nationalism and Imperialism

- By the late 19th century, nationalism became a narrow creed with limited ends, and groups became intolerant of each other.

- The Balkans Crisis: The most explosive region. A large part was under the Ottoman Empire, which was disintegrating. Different Slavic nationalities (Slavs) struggled for independence and territory, making the region an area of intense conflict.

- Big Power Rivalry: European powers (Russia, Germany, England, Austro-Hungary) competed for control over the Balkans to further their imperialist aims. This rivalry led to a series of wars, culminating in the First World War in 1914.

- Anti-Imperialism: Colonized countries began to oppose imperial domination, developing their own specific varieties of nationalism, but all accepting the validity of the "nation-state" model.

Quick Navigation:

| | |

1 / 1

Quick Navigation:

| | |